There are three major competing Greek sources to use for translating the New Testament: the Critical Text, the Majority Text, and the Textus Receptus. The science of assembling these manuscripts is called “Textual Criticism”, and you can consider this a complete Textual Criticism 101 article because we’ll look at these topics in exhaustive detail.

There are three major competing Greek sources to use for translating the New Testament: the Critical Text, the Majority Text, and the Textus Receptus. The science of assembling these manuscripts is called “Textual Criticism”, and you can consider this a complete Textual Criticism 101 article because we’ll look at these topics in exhaustive detail.

And I do mean exhaustive detail.

This is the second longest article on this website (after the one on Revelation), but that’s because it’s extremely complete. After reading this one article, you’ll know more about these topics than the overwhelming vast majority of Christians.

So let’s get started. 🙂

What is Textual Criticism?

Here is an excellent definition of Textual Criticism from Dan Wallace, who is one of the most respected Textual Critics in the world today.

Textual Criticism is:

The study of the copies of a written document whose original (the autograph) is unknown or non-existent, for the primary purpose of determining the exact wording of the original.

The practice of Textual Criticism is not “criticizing the Bible“, it’s trying to recover the Bible’s original text. A “textual critic” is not someone who criticizes the Bible, but someone who tries his best to reconstruct the original text.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, but we don’t have the original documents that Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Paul, and other New Testament writers wrote. They were originally written on either papyrus (essentially paper) or possibly parchment (animal skins) which have long since degraded with time and use. However, the originals were copied many, many times. Those copies were copied, which were copied, which were copied, which were…

Well, you get the idea.

So what we have are copies of copies of the original (sometimes many generations of copying deep). Before Gutenberg invented the printing press in the early-mid 1400s, everything was copied by hand. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the scribes who did the copying occasionally made some mistakes.

When two copies disagree with each other, you have a variant in the text between two documents: this is (unsurprisingly) called a “Textual Variant”.

Clever, right? 😉

What “Textual Variants”? How bad are They?

Fortunately, they just aren’t that bad. 🙂 We can broadly class all Textual Variants into two classes.

- Meaningful Variants. These textual variants have an impact on what the text means. For example, if one manuscript says”Jesus was happy” and another says “Jesus was sad”, that’s a meaningful variant because it changes the meaning of the text.

- Viable Variants. These Textual Variants have a decent chance of having the wording of the original document. Some variants appear in only a single (late) manuscript, and thus the chances of them being in the original text are extremely low.

From those two options, we can create a list of four types of Textual Variant.

- Neither meaningful nor viable (they don’t change the meaning and have no chance of being original)

- Viable but not meaningful (they don’t change the meaning and have a chance of being original)

- Meaningful but Not viable (they do change the meaning, but have no chance of being original)

- Both Viable and meaningful (they do change the meaning and do have a chance of being original)

We’ll look at #1 and #2 two together

Textual Variants that are NOT meaningful, even if viable.

These are Textual Variants that have no effect on anything. These comprise over 75% of all textual variants, which means over 75% of textual variants have no effect on anything whatsoever.

In fact, the most common type of Textual Variant is spelling differences, often a single letter. Remember, there was no dictionary in ancient times, and thus no defined right or wrong way to spell a word. The single most common textual variant is called a “moveable Nu“, with “Nu” being the Greek letter that sounds like our “N”.

In English, we have this rule too. (Sort of).

In English the indefinite article “a” gets an “n” added when the next word starts with a vowel. For example:

- “This is a book.”

- “This is an owl.”

Greek applies this rule more frequently, and that’s the most common textual variant. Does it matter much if Paul wrote “a owl” vs “an “owl”? Exactly. It simply doesn’t matter to the meaning. In fact, this Textual Variant (movable Nu) is the single most common Textual Variant.

Other examples include when one manuscript has “Jesus Christ”, and another has “Christ Jesus”, with only the order changed. Again, it simply doesn’t matter which is original because there’s no impact on meaning. (You’ll know this is especially true of Greek if you’ve read my A Few Fun Things About Biblical (Koine) Greek article) Another example: perhaps one document will only have “Christ” and another only has “Jesus”. Again, this doesn’t change the meaning much, even if it does change the text slightly.

Again, over 75% of all Textual Variants are not meaningful, even if they are viable. (Viable = possibly original)

So don’t worry, your Bible isn’t filled with mistakes. 🙂

Textual Variants that are Meaningful, but not viable.

These are variants where it’s essentially impossible for them to have been original, even if they would change the meaning of the text. Typically, these variants are found only in a single manuscript, or in a small group of manuscripts from one small part of the world. Most often, they are simple scribal errors.

I have a rather humorous example:

1 Thessalonians 2:7

But we proved to be gentle among you, as a nursing mother tenderly cares for her own children.

There’s a Textual Variant for the word “gentle”. Most manuscripts read “gentle”, some read “little children” and one manuscript reads “horses”. It’s easy to explain these variants when you see how these words are spelled in Greek, so here are the first three words of the verse in each Textual Variant:

- Alla Egenēthēmen ēpioi (gentle)

- Alla Egenēthēmen nēpioi (little children)

- Alla Egenēthēmen hippioi (horses)

Context tells us that nēpioi (little children) can’t be intended, and since the previous word begins with “n”, it’s easy to see how the mistake was made (doubling the “n”). Often, one scribe would read while several other scribes copied. If you heard it read, you’d realize it’s an easy mistake to make because they sound almost identical. (Because the previous word ends with an “n” sound)

Further, there’s no possible way that hippioi (horses) was intended. It was a simple scribal error, easily noticed and just as easily corrected. (With a good chuckle. 🙂 ) Both Textual Variants are meaningful, but it’s nearly impossible for them to be original (they aren’t viable).

These types of Textual Variants make up ~24% of all Textual Variants.

Combined with the ones that aren’t meaningful, you have over 99% of all Textual Variants make no impact on meaning whatsoever.

Pretty cool right? 🙂

Textual Variants that are Meaningful and Viable

These Textual Variants have a good chance of being original (viable), and change the meaning of the text (meaningful). They comprise less than 1% of all Textual Variants.

We’ve examined one of these Textual Variants here on Berean Patriot before, namely: The Johannine Comma of 1 John 5:7-8: Added or Removed? Other major Textual Variants include the story of the woman caught in Adultery (also called the “Pericope Adulterae”, and I do have an article on if it’s original or not) and the last 12 verses in Mark’s Gospel (I have an article on that as well). Those three are probably the most well-known, but there are many more.

Next, we’ll look at the three competing theories on how to handle the less-than-1% of places where the text of the New Testament isn’t completely agreed up on.

The Three Competing Theories – Overview

Here is a short summary of each theory, with more detail to follow in each theory’s section.

“Reasoned Eclecticism” or the “Critical Text” Theory

This method applies a series of rules to the various manuscripts we’ve found (we’ll look at those rules in a moment). Using these rules – and a healthy dose of scholarly input – they decide what was likely added, removed, or changed, and therefore what’s likely original. The result is called a “Critical Text”. This is the position held by a majority of New Testament Scholars, and nearly all modern Bibles are translated from the Critical Text.

The Majority Text Theory

Majority Text scholars take a more mathematical approach to deciding what the original text of the New Testament was. Their approach is to take all the manuscripts we have, find which Textual Variant has support among the majority of manuscripts, and give that reading priority. This is based on the assumption that scribes will choose to copy good manuscripts over bad ones, and thus better readings will be in the majority over time. There are good mathematical reasons for this method (which we’ll look at lower down). Because most of our New Testament manuscripts come from the Byzantine Text family (which we’ll explain lower down), the document that results is often called the “Byzantine Majority text”.

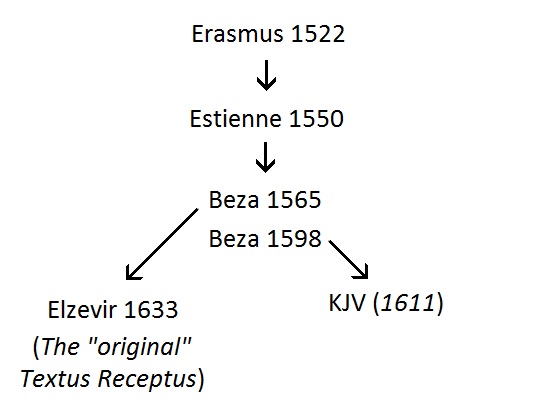

The “Confessional” Position, or “Textus Receptus Only”

This position takes its name from where it starts: a “confession of faith”. The Confessional view holds that God must have preserved the scriptures completely without error. (We’ll look at the verses they use to support this statement lower down.) They believe that God kept one particular text completely free of error, and that text is the Textus Receptus. The Textus Receptus is a 16th-century Greek New Testament on which the King James Bible is based (in the New Testament). They will typically only use the King James Bible (KJV) or New King James Bible (NKJV) as an English translation, but some will only accept the KJV.

Now that we have a basic overview, we’ll look at each theory in (exhaustive) detail. Again, this is one of the longest articles on this website, but it’s so long because the topic is complex and our treatment of it is fairly complete. Hopefully, this can be a “one stop shop” for anyone wishing for an introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism.

Before we look at each theory though, we need to understand what are called “text types”

New Testament Textual Families or “Text Types”

Among the existing manuscripts of the New Testament, there are three major divisions based on their content. These divisions aren’t hard and fast, but rather provide a framework to talk about the different Textual Variants.

Each textual family (or “text type”) tends to contain similar readings to other manuscripts in its family, but the readings are different from the readings of other textual families. (Again, in that less than 1% where it matters) Notice they only “tend to”. There are variations within each family, but overall, their Textual Variants share a familial linkage with other members of their family.

There are three major textual families/text types.

Alexandrian Text Type

The Alexandrian text type will need little introduction because nearly all modern Bibles are based on the Alexandrian text type. If you pick up any popular Bible (except the KJV and NKJV) it’s almost certainly translated primarily from the Alexandrian text type. Almost all of the oldest manuscripts we have are of the Alexandrian text type, probably due to the climate in the location where they are typically found (Alexandrian is in Egypt, and its dry climate is ideal for preservation.) The Alexandrian text type is slightly shorter than the Byzantine text type.

Western Text Type

The Western text type is different from the other textual families mostly because of its “love of paraphrase”. One scholar said of the Western text type: “Words and even clauses are changed, omitted, and inserted with surprising freedom, wherever it seemed that the meaning could be brought out with greater force and definiteness.” Unsurprisingly, they aren’t given too much weight because of this freeness. Further, we have relatively few Western text-type manuscripts.

Byzantine Text Type

We have more manuscripts of the Byzantine text type by far than the other two families combined. Robinson-Pierpont said in their introduction to their Greek New Testament “Of the over 5000 total continuous-text and lectionary manuscripts, 90% or more contain a basically Byzantine Text form“. However, the majority of these manuscripts are later than Alexandrian manuscripts. The Byzantine text type does have some very early witnesses, (in papyri from the 200s and 300s) but these often contain Byzantine readings mixed in with the other text types. The Byzantine text type is noticeably longer than the Alexandrian text type.

(Note: the Byzantine Text type has several names, including the Traditional Text, Ecclesiastical Text, Constantinopolitan Text, Antiocheian Text, and Syrian Text.)

Now that you understand the three text types/families, we’ll move onto discussing the most popular of the three theories.

The “Critical Text” Theory, aka “Reasoned Eclecticism”

Reasoned Eclecticism uses a set of rules to sift through all the Textual Variants and arrive at what they believe is original. Since the rules are so central to their philosophy, we’ll take some time to examine them. Further, understanding how these rules work and their place in Bible history will help you understand the modern Critical Text.

The Rules of Textual Criticism According to Reasoned Eclecticism

There are several different sets of rules for Reasoned Eclecticism. (You can look at several here.) However, we’ll only concentrate on the two most influential. Those are the Westcott & Hort rules, and the Aland/Aland Rules.

In 1881, Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort published “The New Testament in the Original Greek“, which is the grandfather of the Greek Critical Text that most modern Bibles translate from. It’s so well known that it’s often just called “Westcott & Hort”.

Their rules for textual Criticism are below:

(Note: I condensed these from here, at the bottom of the page.)

- Older readings, manuscripts, or manuscript groups should be preferred

- Readings are approved or rejected by reason of the quality, and not the number, of their supporting witnesses

- A reading combining two simple, alternative readings is later than the two readings comprising the combination. Manuscripts that rarely or never combine readings are of “special value”.

- The reading that best conforms to the grammar and context of the sentence should be preferred

- The reading that best conforms to the style and content of the author should be preferred

- The reading that explains the existence of other readings should be preferred.

- A reading that shows better grammar at the expense of theology is likely not original.

- The more difficult reading should be preferred.

- Prefer readings in manuscripts that habitually contain better readings, which is more certain if it’s also an older manuscript and if it doesn’t contain combinations of other variations (as in rule #3). This also applies to manuscript families.

Please notice, Westcott & Hort’s first rule is basically “older is better”. (Majority Text advocates disagree, but we’ll look at their objection later.) Now, because all the oldest manuscripts we’ve found are of the Alexandrian text type/family, it’s unsurprising that they ended up with a basically Alexandrian document. Further, they didn’t include any Western or Byzantine readings on purpose.

Why?

Well, remember how the Western text type was famous for paraphrasing and the quote for it? Well, it was Westcott & Hort who said of the Western text: “Words and even clauses are changed, omitted, and inserted with surprising freedom, wherever it seemed that the meaning could be brought out with greater force and definiteness.” Therefore, it shouldn’t be surprising that they basically ignored the Western text type.

They are rarely – if ever – faulted for that.

To understand why they didn’t use any Byzantine readings, we need to look at their 3rd rule again: “A reading combining two simple, alternative readings is later than the two readings comprising the combination.” Further, remember that “latter readings” were ignored by Westcott & Hort.

So here’s the why:

Westcott & Hort believed the Byzantine text type was a combination of the Alexandrian and Western text types.

More recent manuscript findings have proved this wrong, but more on that later. Westcott & Hort thought the Byzantine text family resulted from some scribes combining the other two text types to try and get closer to the original document (much like they were doing).

Remember the rules:

- If the Byzantine text type was a combination of the Alexandrian and Western text types,

- And if “combination” manuscripts were always later, (rule #3)

- And if “earlier is better” (rule #1)

- Then the Byzantine text type should be ignored as a latter, less-authentic text type.

So that’s exactly what they did.

They ignored all Byzantine readings and rejected them as being later and therefore not worth looking at. In their own words:

“All distinctively Syrian (Byzantine) readings must be at once rejected.” – Westcott & Hort

Again, in the last 100+ years, we’ve found manuscripts that prove the Byzantine text type isn’t a combination of the Western and Alexandrian text types. Unfortunately, this bias against Byzantine readings persisted until later, to Kurt Aland. (He was the primary editor of the modern Critical Text, which is the basis for nearly all modern translations.)

In a similar vein, Kurt Aland considers Greek manuscripts which are “purely or predominately Byzantine” to be “irrelevant for textual criticism.”

Again, Westcott and Hort were mistaken as nearly all major textual variants had appeared before the year 200. From another article on the topic:

However, Hort acknowledged that such a clear-cut genealogical model would be out of place if a transmission-model persistently involved readings which all had some clearly ancient attestation. [See Hort’s Introduction, page 286, § 373.]

This very thing, or something very close to it, was subsequently proposed by textual critics in the 1900’s. Eminent scholars such as E. C. Colwell, G. D. Kilpatrick, and Kurt and Barbara Aland maintained, respectively, that “The overwhelming majority of readings,” “almost all variants,” and “practically all the substantive variants in the text of the New Testament” existed before the year 200. Nevertheless the Hortian text has not been overthrown.

Again, the Westcott & Hort Critical Text is the grandfather of nearly all modern Bibles, KJV and NKJV excepted. We’ll look more at how we got to the present Greek Critical Text soon.

As an aside:

There remains a persistent bias against the Byzantine Text type in Reasoned Eclecticism/Critical Text advocates. Here’s Dan Wallace – arguably the most respected New Testament textual critic alive today – talking about one of our oldest manuscripts, specifically Codex Alexandrius.

“Codex Alexandrius is a very interesting manuscript in that in the Gospels, it’s a Byzantine text largely, which means it agrees with the majority of manuscripts most of the time. While as, in the rest of the New Testament, it is largely Alexandrian. These are the two most competing textual forms, textual families, text types if you want to call them that, that we have for our New Testament manuscripts. So when you get outside the Gospels, Alexandrius becomes a very important manuscript.” – Dan Wallace

Source: YouTube. (Only 1:35 long, starting at about 0:53)

Please notice the casual dismissal of the Byzantine text type by one of the most respected textual critics of our age. I’m honestly not sure why it’s dismissed so easily. Codex Alexandrius is the third oldest (nearly) complete manuscript, dating from the early 400s. Why dismiss the Gospels just because they are a different text type?

But I digress…

The Aland Rules of Textual Criticism

We won’t spend much time on these because the Westcott & Hort rules were more influential. However, they’re worth noting.

The “Aland” rules get their name from Kurt and Barbara Aland, who were instrumental in the publication of the Greek Critical Text that nearly all modern New Testament are based on: The Nestle-Aland “Novum Testamentum Graece” (The New Testament in Greek)

The first edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece was published by Eberhard Nestle in 1898, but an updated version was introduced in 1901. It was a combination of primarily Westcott & Hott’s work, along with two other Greek New Testaments. Later it was taken over by his son, and eventually by Kurt Aland and his wife, along with others. It’s commonly referred to as the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece after the two most significant contributors. (Eberhard Nestle and Kurt Aland)

It’s often abbreviated as “NA” plus the version number, for example: “NA28”. It’s currently in its 28th edition (as of spring 2020).

The Aland rules generally follow the Westcott & Hort rules with one major difference. I’ve copy/pasted the two rules that conflict just below:

Westcott & Hort rule #9: Prefer readings in manuscripts that habitually contain better readings, which is more certain if it’s also an older manuscript and if it doesn’t contain combinations of other variations (as in rule #3). This also applies to manuscript families.

Aland rule #6: Furthermore, manuscripts should be weighed, not counted, and the peculiar traits of each manuscript should be duly considered. However important the early papyri, or a particular uncial, or a minuscule may be, there is no single manuscript or group or manuscripts that can be followed mechanically, even though certain combinations of witnesses may deserve a greater degree of confidence than others. Rather, decisions in textual criticism must be worked out afresh, passage by passage (the local principle).

(Note: I’ve copy/pasted the only relevant difference, but you can: Click here to expand the full list of the Aland rules of Textual Criticism.)Click here to collapse the full list of the Aland rules of Textual Criticism.)

- Only one reading can be original, however many variant readings there may be.

- Only the reading which best satisfies the requirements of both external and internal criteria can be original.

- Criticism of the text must always begin from the evidence of the manuscript tradition and only afterward turn to a consideration of internal criteria.

- Internal criteria (the context of the passage, its style and vocabulary, the theological environment of the author, etc.) can never be the sole basis for a critical decision, especially when they stand in opposition to the external evidence.

- The primary authority for a critical textual decision lies with the Greek manuscript tradition, with the version and Fathers serving no more than a supplementary and corroborative function, particularly in passages where their underlying Greek text cannot be reconstructed with absolute certainty.

- Furthermore, manuscripts should be weighed, not counted, and the peculiar traits of each manuscript should be duly considered. However important the early papyri, or a particular uncial, or a minuscule may be, there is no single manuscript or group or manuscripts that can be followed mechanically, even though certain combinations of witnesses may deserve a greater degree of confidence than others. Rather, decisions in textual criticism must be worked out afresh, passage by passage (the local principle).

- The principle that the original reading may be found in any single manuscript or version when it stands alone or nearly alone is only a theoretical possibility. Any form of eclecticism which accepts this principle will hardly succeed in establishing the original text of the New Testament; it will only confirm the view of the text which it presupposes.

- The reconstruction of a stemma of readings for each variant (the genealogical principle) is an extremely important device, because the reading which can most easily explain the derivation of the other forms is itself most likely the original.

- Variants must never be treated in isolation, but always considered in the context of the tradition. Otherwise there is too great a danger of reconstructing a “test tube text” which never existed at any time or place.

- There is truth in the maxim: lectio difficilior lectio potior (“the more difficult reading is the more probable reading”). But this principle must not be taken too mechanically, with the most difficult reading (lectio difficilima) adopted as original simply because of its degree of difficulty.

- The venerable maxim lectio brevior lectio potior (“the shorter reading is the more probable reading”) is certainly right in many instances. But here again the principle cannot be applied mechanically.

- A constantly maintained familiarity with New Testament manuscripts themselves is the best training for textual criticism. In textual criticism the pure theoretician has often done more harm than good.

Westcott & Hort preferred to take manuscripts they deemed “more reliable” (read: “early and Alexandrian”) and rely on their readings more. However, Aland took the opposite approach, preferring to look at all the evidence in each passage separately. These different philosophies naturally produced slightly different results…

…but only slightly different

Overall, the Critical Text of the modern Greek New Testament bears a remarkable resemblance to the original work done by Westcott & Hort. The following is a quote from the (excellent) blog The Text of the Gospels, doing a comparison of Westcott & Hort’s original 1881 text (WH1881) to the modern NA27 (Nestle-Aland 27th edition) and NA28. (34 readings were changed from the NA27 to the NA28)

Adding to this the 34 new readings in NA28, the total number of full disagreements in the 28th edition of Novum Testamentum Graece against WH1881 is 695.

This is particularly interesting when one turns to the Editionum Differentiae (Appendix III) in the 27th edition of NTG, which lists (among other things) the differences between NA27 and NA25. (The text was essentially unchanged in the intervening 26th edition, which had essentially the same text as the third edition of the UBS Greek New Testament.) There one can observe that between NA25 and NA27, there were 397 changes in the Gospels, 119 in Acts, 149 in the Pauline Epistles, 46 in the General Epistles, and 29 in Revelation, for a total of 740.

(Emphasis added)

The modern NA27 and NA28 are closer to Westcott & Hort’s 1881 text than the NA25.

The reason we’ve spent so much time talking about Westcott & Hort is because the New Testament Critical Text that nearly all modern Bibles are based on is virtually unchanged since 1881. Now, that could be a good thing if you believe Westcott & Hort did a good job originally.

So we’ll look at their methodology, and the methodology of Reasoned Eclecticism in general.

Reasoned Eclecticism Methodology

Again, we’ll go back to Westcott & Hort because they did the original work that virtually all modern New Testament translations are based on. Remember, their #1 rule was “earlier is better”. Consequently, their New Testament relied heavily on the two earliest (nearly) complete manuscripts we have:

Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, which we’ll look at in detail shortly

Since these were the two oldest (nearly) complete texts available at the time, Westcott & Hort gave them tremendous weight. Remember their #1 rule was “Older is better”. And if “older is better”, then it follows logically that the two oldest manuscripts are the best. (Others disagree, but we’ll get to those arguments later.)

There is a system for naming manuscripts of the New Testament. In this system, Codex Vaticanus is also called manuscript “B”, and Codex Sinaiticus is also called manuscript “א” (aleph, which is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet)

Westcott & Hort believed that any place where those two manuscripts agreed:

“…should be accepted as the true readings until strong internal evidence is found to the contrary,”

They also said of where those two manuscripts agreed:

“No readings of אB can safely be rejected absolutely,”

Yes, they believed these two manuscripts were that important, and this understanding follows naturally if you believe their #1 rule that “earlier is better”. (Which many dispute, but we’ll get to that later.)

These two codices – Codex Vaticanus (“B”) and Codex Sinaiticus (“א”) – are the foundation for nearly all modern New Testaments.

We have 5000+ manuscripts of the New Testament, though many are smaller fragments. In the last ~140 years since the Westcott & Hort 1881 Critical Text, we’ve discovered Papyri from the 300s, 200s, and even a few from the 100s. Despite this, the Critical Text of the New Testament remains virtually unchanged from ~140 years ago.

No joke.

In fact, when you see a Bible footnote that says “the earliest and best manuscripts”, they are almost universally talking about these two manuscripts, and only these two manuscripts.

Please remember that.

It is no exaggeration to say that Codex Vaticanus (“B”) and Codex Sinaiticus (“א”) are the foundation for virtually all modern New Testament Bible translations. Because these manuscripts are so foundational to modern Critical Text, they bear a closer look.

Codex Vaticanus – aka Codex “B”

The Codex Vaticanus gets its name from the place where it was stored, the Vatican library. It is regarded as the oldest extant (existing) Greek copy of the Bible and has been dated to the early-mid 4th century. It’s over 90% intact/complete, which is incredible for a manuscript of its age.

The Codex Vaticanus also contains several of the deuterocanonical books, namely: the Book of Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Judith, Tobit, Baruch, and the Letter to Jeremiah. (There’s an article about these other books here on Berean Patriot entitled: The Bible: 66 books vs 73 and Why (the “Apocrypha” Explained).)

Codex Vaticanus (“B”) is an excellent example of the Alexandrian Text type, and many scholars think it’s the most important Greek manuscript we have (again because it’s the oldest). In fact, the primary author/editor of the modern Critical Text (Kurt Aland) said this:

“B is by far the most significant of the uncials” – Kurt Aland

Source: “The Text of the New Testament” By Aland

(Note: “Uncials” is the plural of “uncial”, which refers to an all-capital font. We have four nearly complete Uncial manuscripts dating from before the year 1000. These four are often called the “Great Uncial Manuscripts”)

It’s curious that Codex Vaticanus is given the position of “most important” when the actual quality of the transcription leaves something to be desired.

Dean Burgon describes the quality of the scribal work in Vaticanus:

Codex B [Vaticanus] comes to us without a history: without recommendation of any kind, except that of its antiquity. It bears traces of careless transcription in every page. The mistakes which the original transcriber made are of perpetual recurrence.

The New Westminster Dictionary of the Bible concurs,

“It should be noted, however, that there is no prominent Biblical MS. in which there occur such gross cases of misspelling, faulty grammar, and omission, as in B [Vaticanus].”

Now, I think they are overstating the case slightly (as you’ll see when we look at Codex Sinaiticus). But the principle remains that the Vaticanus scribe certainly wasn’t top tier. Some scholars would say he wasn’t even middle of the pack. Probably the most balanced view of the Vaticanus scribe is found in the quote below, in an article published to respond to someone claiming the Vaticanus Scribe made very few errors.

It seems to me that while the scribe of Codex Vaticanus is certainly not the worst scribe ever (a title that must go to the scribe of Old Latin Codex Bobbiensis), his execution leaves something to be desired, and the claim that he hardly ever made blunders must be regarded as an exaggeration.

Source. (Emphasis added)

In the 10th or 11th century, at least two scribes made corrections to the Codex Vaticanus. This isn’t altogether uncommon with ancient manuscripts, but it does mean some places represent a 10th or 11th-century version, not a 4th-century version.

That leads to the possibly the most humorous – and unsettling – thing about these correctors: the addition of a rebuke by one corrector to another.

The copyist of Codex Vaticanus had written Φανερων in Hebrews 1:3, and a corrector had replaced that with the correct reading, Φέρων (which is supported by all other manuscripts, including Papyrus 46). The person who wrote this note, however, objected to this correction, and wrote, ἀμαθέστατε καὶ κακέ, ἂφες τὸν παλαιόν, μὴ μεταποίει. Metzger translated these words as, “Fool and knave, can’t you leave the old reading alone, and not alter it!” Another rendering: “Untrained troublemaker, forgive the ancient [reading]; do not convert it.” He re-wrote Φανερων, erasing most of the corrector’s Φερων. Apparently, the note-writer regarded Codex Vaticanus as a museum-piece to be protected and preserved, rather than as a copy of Scripture to be used as such.

Source. (Emphasis added)

To be clear, the scribal quality of Codex Vaticanus isn’t terrible, but neither is it incredible. Mediocre might be the best description, though some would say “poor”. There is some disagreement on the actual level of quality.

Again, Codex Vaticanus is regarded as the single best New Testament manuscript by the adherents of the Reasoned Eclecticism/Critical Text theory. There are only two reasons for this: (1) it’s nearly complete, and (2) the “older is better” mantra.

Codex Sinaiticus – aka Codex “א”

Codex Sinaiticus takes its name from where it was found: at the base of Mount Sinai. Sadly, there is much propaganda and misinformation regarding its discovery. Many claim it was “found in the trash” while others claim it was carefully preserved by monks. To dispel the confusion, I’m going to quote from the primary source: the finder’s own account of how he found it.

Codex Sinaiticus was found by a man named Lobegott Friedrich Constantin (von) Tischendorf, at St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai. You can read Tischendorf’s entire account of finding it – in his own words – here. The two relevant excerpts are below.

It was at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the Convent of St. Catherine, that I discovered the pearl of all my researches. In visiting the library of the monastery, in the month of May, 1844, I perceived in the middle of the great hall a large and wide basket full of old parchments; and the librarian, who was a man of information, told me that two heaps of papers like these, mouldered by time, had been already committed to the flames. What was my surprise to find amid this heap of papers a considerable number of sheets of a copy of the Old Testament in Greek, which seemed to me to be one of the most ancient that I had ever seen. The authorities of the convent allowed me to possess myself of a third of these parchments, or about forty-three sheets, all the more readily as they were destined for the fire. But I could not get them to yield up possession of the remainder. The too lively satisfaction which I had displayed had aroused their suspicions as to the value of this manuscript.

He was able to view 43 sheets, which was a third of the sheets that were to be burned. Therefore, ~130 pages were going to be burned. It’s worth noting that Codex Sinaiticus is far longer than 130 pages. The British museum has 694 pages, which is over half the original length.

So no, the entire Codex Sinaiticus wasn’t going to be burned.

It seems likely from Tischendorf’s description that only some worn-out pages from Sinaiticus were going to be burned, but it’s hard to be sure. Tischendorf himself might not have been sure.

He returned to the monastery some 15 years later, partially in hopes of recovering the manuscript.

On the afternoon of this day I was taking a walk with the steward of the convent in the neighbourhood, and as we returned, towards sunset, he begged me to take some refreshment with him in his cell. Scarcely had he entered the room, when, resuming our former subject of conversation, he said: “And I, too, have read a Septuagint“–i.e. a copy of the Greek translation made by the Seventy. And so saying, he took down from the corner of the room a bulky kind of volume, wrapped up in a red cloth, and laid it before me. I unrolled the cover, and discovered, to my great surprise, not only those very fragments which, fifteen years before, I had taken out of the basket, but also other parts of the Old Testament, the New Testament complete, and, in addition, the Epistle of Barnabas and a part of the Pastor of Hermas.

From this account, the accusation that “it was found in a wastepaper basket/trash can” is technically true, but is rather misleading. It seems obvious that the entire thing wasn’t going to be burned.

BTW, you can read all of Codex Sinaiticus online if you wish at the Codex Sinaiticus Project website.

Now, about the quality of Codex Sinaiticus.

Even those who love the manuscript will admit it has serious quality problems. Even the official Codex Sinaiticus Project website (link above) admits this:

No other early manuscript of the Christian Bible has been so extensively corrected. A glance at the transcription will show just how common these corrections are. They are especially frequent in the Septuagint portion. They range in date from those made by the original scribes in the fourth century to ones made in the twelfth century. They range from the alteration of a single letter to the insertion of whole sentences.

They aren’t the only ones to say this either. The manuscript’s finder Tischendorf – who reckoned it as the greatest find of his life – said the following:

On nearly every page of the manuscript there are corrections and revisions, done by 10 different people.

Tischendorf also said that he: “counted 14,800 alterations and corrections in Sinaiticus.” He goes on to say:

The New Testament…is extremely unreliable…on many occasions 10, 20, 30, 40, words are dropped…letters, words, even whole sentences are frequently written twice over, or begun and immediately canceled. That gross blunder, whereby a clause is omitted because it happens to end in the same word as the clause preceding, occurs no less than 115 times in the New Testament.

By any conceivable metric (except age), Codex Sinaiticus is one of the worst manuscripts that we’ve found. You probably couldn’t find a scholar who would praise the scribal work in Sinaiticus, and it’s easy to find those who deride it as the worst scribal work among the manuscripts we’ve found.

Comparing Vaticanus and Sinaiticus

As we’ve just seen, Codex Vaticanus is a mediocre-to-poor quality manuscript. Codex Sinaiticus is among the worst manuscripts we have. Now, we’ll look at how they compare to each other, and how much they agree with each other.

(Note: the “He” in the quote below is Dean Burgon)

He also checked these manuscripts for particular readings, or readings that are found ONLY in that manuscript. In the Gospels alone, Vaticanus has 197 particular readings, while Sinaiticus has 443. A particular reading signifies one that is most definitely false. Manuscripts repeatedly proven to have incorrect readings loose respectability. Thus, manuscripts boasting significant numbers of particular readings cannot be relied upon.

The Textual Variants between them are numerous.

According to Herman C. Hoskier, there are, without counting errors of iotacism, 3,036 textual variations between Sinaiticus and Vaticanus in the text of the Gospels alone

Assuming that the same ratio of variants persists in the rest of the New Testament and doing the math, that’s ~3434 additional variants, for a total of ~6470 variants between them. There are 7956 verses in the New Testament. That’s an average of 0.81 variants per verse between Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. Therefore, roughly 4 out of every 5 verses (81.3%) in one manuscript disagrees with the other manuscript in at least one place. (On average. In reality, the distribution is never that perfect.)

According to Dean Burgon:

“It is in fact easier to find two consecutive verses in which these two MSS differ the one from the other, than two consecutive verses in which they entirely agree.”

Despite the numerous Textual Variants between them, there’s an interesting theory about their origin.

The manuscript is believed to have been housed in Caesarea in the 6th century, together with the Codex Sinaiticus, as they have the same unique divisions of chapters in Acts.

There’s no other evidence for this – so take it with a grain of salt – but they are the only two manuscripts that share that characteristic. The fact that they share a unique characteristic makes it more likely they came from the same general area. That’s pure theory without other evidence, but it’s interesting.

Corruption of the Alexandrian text type?

I’m almost hesitant to include this, as it comes close to an Ad Hominem attack on the entire Alexandrian Text type/family. However, I have included it for completeness.

The following is regarding the Alexandrian text-type manuscripts.

However, the antiquity of these manuscripts is no indication of reliability because a prominent church father in Alexandria testified that manuscripts were already corrupt by the third century. Origen, the Alexandrian church father in the early third century, said:

“…the differences among the manuscripts [of the Gospels] have become great, either through the negligence of some copyists or through the perverse audacity of others; they either neglect to check over what they have transcribed, or, in the process of checking, they lengthen or shorten, as they please.”

(Bruce Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3rd ed. (1991), pp. 151-152).

Origen is of course speaking of the manuscripts of his location, Alexandria, Egypt. By an Alexandrian Church father’s own admission, manuscripts in Alexandria by 200 AD were already corrupt. Irenaeus in the 2nd century, though not in Alexandria, made a similar admission on the state of corruption among New Testament manuscripts. Daniel B. Wallace says, “Revelation was copied less often than any other book of the NT, and yet Irenaeus admits that it was already corrupted — within just a few decades of the writing of the Apocalypse”

There’s an argument to be made that the Alexandrian Text type was corrupted very early. It’s by no means an ironclad argument, but I would’ve been remiss if we didn’t talk about it here. (We’ll come back to it later.)

Westcott & Hort had… questionable beliefs?

There is some evidence that Westcott & Hort didn’t have a high opinion of the Bible. There’s further evidence – based on quotes they said – that they didn’t take the Bible seriously, literally, and endorsed the Theory of Evolution.

However, to simply say their Critical Text is bad because of their personal views is… problematic.

While the character of the workers can shed some light on the work, I prefer to judge a work based on its merits, not what the authors might have believed. Therefore, if this line of reasoning interests you, you can read more here. I will devote no more space to it in this article because I don’t think it’s relevant, and only mentioned it for completeness.

The one thing I will mention is Hort at least was motivated to eliminate the Textus Receptus from the public eye, as he considered it “vile”.

“I had no idea till the last few weeks of the importance of text, having read so little Greek Testament, and dragged on with the villainous Textus Receptus … Think of the vile Textus Receptus leaning entirely on late MSS; it is a blessing there are such early ones.” – Fenton Hort

Again, this is because of his “earlier is better” philosophy.

Reasoned Eclecticism / Critical Text Conclusion

In the end, the greatest strength of the Critical Text is also its greatest weakness: man’s involvement. If you forced me to pick one of the three major theories (instead of the blend I prefer) I’d pick Reasoned Eclecticism… but with a different set of rules.

The problem was Westcott & Hort’s application of the theory.

The original rules set down by Westcott &Hort aren’t consulted very often anymore. However, their original work is still with us. All the modern Greek Critical Texts bear an extremely strong resemblance to Westcott & Hort’s original 1881 Critical Text. Their text was heavily based on the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus. These two documents are rather flawed, especially Sinaiticus.

They also discounted the entire Byzantine text type based on an assumption which has now been proved wrong. Despite the Byzantine text type being vindicated by extremely early manuscript findings, there remains a persistent bias against Byzantine readings for no apparent reason.

Further, it means all the manuscript findings of the last 140+ years are given very little consideration in modern Bibles.

Personally, I think that’s a problem.

To be clear, the theory of Reasoned Eclecticism is sound; it’s the application of it (thus far) that leaves something to be desired.

Please don’t mistake the one for the other.

The modern Critical Text is based primarily on two flawed documents, without the benefit of the findings of the last ~140 years. If you could alter the rules – or simply remove the bias against the Byzantine text type – Reasoned Eclecticism stands a very good chance of producing the best results.

The Majority Text Theory

Einstein once said:

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

The Majority Text theory is that to a “T”. It’s simplicity itself, but under-girding that simplicity is profound sophistication. It definitely has flaws (which we’ll discuss later), but it also has some significant strengths.

What is the Majority Text methodology?

The basic premise is extremely simple:

“Any reading overwhelmingly attested by the manuscript tradition is more likely to be original than its rival(s).”

Source: The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text, p. xi.

Essentially, whenever one reading has more manuscripts supporting it than the other variants readings, it’s more likely to be the original reading. Or to put it another way:

The Majority Text method within textual criticism could be called the “democratic” method. Essentially, each Greek manuscript has one vote, all the variants are voted on by all the manuscripts, and whichever variant has the most votes wins.

It might sound simplistic, but there’s a good mathematical reason and a good common sense reason behind it.

Further – and I can’t stress this enough – there is more to the Majority Text theory than simply counting manuscripts.

At face value, that’s it.

However, real Textual Criticism with a set of rules still must be applied. Very few – if any – scholars would argue that the Majority wins all the time. You still need to sift through the manuscripts and apply a more careful methodology than simple “nose counting”. We’ll talk more about this later.

For now, we’ll look at the underpinnings of the Majority Text theory.

Note: it will sound like I’m strongly biased in favor of the Majority Text while I present the “pro” side of the argument. I’m not. It has significant downsides which we’ll look at after the “pro” side.

The Mathematical Case for The Majority Text

This is easiest to explain with an example.

Several of Paul’s letters were encyclical, meaning they were intended to be passed around from church to church. So let’s say one of Paul’s letters arrives at your church and you’re supposed to pass it on. However, you’d like to keep a copy, so you hire a scribe to copy the letter before passing it on.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume the letter went to five churches, and then is accidentally destroyed. Now you have five copies in five different locations, but no original. Further, let’s assume that each scribe accidentally made a different error while copying, as happens when copying by hand.

The odds of all the scribes making the same error are extremely low. Even if two scribes (40%) did, the majority of scribes (60%) will have preserved the correct reading.

Now, let’s take it a step further.

Let’s say that the five original copies each had five copies made of them, all made by faithful scribes. That brings us to 30 total manuscripts. Further, we’ll assume the “persistence of errors”, meaning faithful scribes will copy even the errors of previous scribes.

Again, the odds of all those scribes making the same error is vanishingly low. (In most cases, more on that in a minute)

Now, let’s assume at this point intentional corruptions enter into the manuscripts that were copied from those 30. Let’s say 2 or 3 scribes start making changes to suit their own theological biases. Under ordinary circumstances, they will never be able to outnumber the scribes who tried to be faithful.

Further (unless they are working in concert) the odds of them coming up with identical changes is minuscule. So instead of creating a new popular reading, they’re more likely to create several unique readings… and even these are in a small minority.

Thus, the theory goes that in most any given time span, the readings in a majority of manuscripts are most likely to reflect the original.

Ironically, Westcott & Hort recognized this too.

As soon as the numbers of a minority exceed what can be explained by accidental coincidence, … their agreement … can only be explained on genealogical grounds. We have thereby passed beyond purely numerical relations, and the necessity of examining the genealogy of both minority and majority has become apparent. A theoretical presumption indeed remains that a majority of extant documents is more likely to represent a majority of ancestral documents at each stage of transmission than vice versa… [but this] presumption is too minute to weight against the smallest tangible evidence of other kinds.

“Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek: With Notes on Selected Readings” by Westcott & Hort.

Notice that Westcott & Hort recognized the Majority Text theory, but then summarily dismissed it saying “the smallest tangible evidence of other kinds” was enough to overthrow it. That seems more like personal bias talking than scholarly work, and it persists to this day. (As we’ve seen)

Interesting, no?

Again, they believed that the Byzantine Text type was a combination of the Alexandrian and Western text types. Thus, they felt free to ignore them (as we’ve already discussed). Their theory has since been categorically proven wrong, partially by new manuscript findings. These findings include – but aren’t limited to – Papyrus from the 200s and 300s.

However, Some say this mathematical model is Wrong

The typical examples of how to break this model are well-covered in this YouTube video. However, the examples leave out one very important factor (which we’ll get to in a moment.)

For example, let’s say we’re copying the shortest book of the New Testament, 3 John with 219 words (in Greek). It seems likely a decent scribe could copy 219 words without error. For a sense of scale, there are exactly 219 words from the beginning of the last quote to the end of the last section. (Don’t ask how much re-writing that took.)

Further, let’s tip this against the Majority Text.

We’ll assume two scribes copy correctly and one incorrectly. Let’s further assume the “persistence of errors”, which assumes every mistake is copied down to every manuscript after it. So each correct manuscript will always spawn 2 more correct manuscripts, but also each incorrect manuscript will spawn 2 more incorrect manuscripts (and no correct manuscripts).

Here’s what we get. (Just for each generation, not cumulatively.)

- 1st generation: 2 correct copies, 1 incorrect copy (2/1 ratio)

- 2nd generation: 4 correct copies, 3 incorrect copies. (1.75/1) ratio)

- 3rd generation: 8 correct copies, 7 incorrect copies (~1/1 ratio)

- 4th generation: 16 correct copies, 22 incorrect copies (~1/1.4 ratio)

- 5th generation: 32 correct copies, 60 incorrect copies (~1/2 ratio)

By the 5th generation, you can see that the number of manuscripts with errors outnumber the ones without errors nearly 2-1.

This looks like it completely destroys the Majority Text theory… but does it?

First, remember that the worst manuscript in the 5th generation has exactly – and only – 5 mistakes (one added every generation). Only 5 mistakes in 219 words is still pretty good. Over a quarter (16) of the incorrect manuscripts will only have a single mistake, most of the rest will only have 2-3.

If you assume the mistakes are fairly randomly distributed, the Majority holds up quite well. Further, remember that 99% of Textual Variants don’t change the meaning, even if they are original. (And many of these variants would be spelling errors.)

Further, this method of disproving the Majority Text makes an incorrect assumption: that errors are tenacious, i.e. that errors never disappear but instead are copied down through the generations. (Which they aren’t.)

The Myth of Tenacity (of errors)

The basic idea is explained below.

On page 78 of The King James Only Controversy, author James White states: “Once a variant reading appears in a manuscript, it doesn’t simply go away. It gets copied and ends up in other manuscripts.” To support this statement, White appealed to Kurt & Barbara Aland’s similar statement: “Once a variant or a new reading enters the tradition it refuses to disappear, persisting (if only in a few manuscripts) and perpetuating itself through the centuries. One of the most striking traits of the New Testament textual tradition is its tenacity.” – Aland & Aland, The Text of the New Testament, p. 56.

However, this can be easily disproved using common sense and a touch of data. For context, a “singular reading” is a Textual Variant that appears in only one manuscript and no other manuscripts whatsoever.

Now consider the mass of evidence against the concept of tenacity: the hundreds of singular readings that appears in ancient manuscripts, but of which there is no trace in later manuscripts. How many such readings are there? Greg Paulson wrote his 2013 thesis on singular readings in the codices Vaticanus (B), Sinaiticus (À), Bezae (D), Ephraemi Rescriptus (C), and Washingtonianus (W) in the Gospel of Matthew, and he mentioned how many singular readings – i.e., readings that do not recur in any other Greek manuscript – each one of these codices has in its text of Matthew. Paulson’s data:

- Vaticanus: 97.

- Sinaiticus: Scribe A: 163.

- Bezae: 259.

- Ephraemi Rescriptus: 75

- Washingtonianus: 112.

I emphasize that these numbers – showing that five important early manuscripts combine to produce a total of 706 singular readings – only taking the text of Matthew into consideration.

And that’s not all the singular readings. If you look at the earlier papyrus, there’s even more singular readings.

Royse provides a chart which conveys that Papyrus 45 has 222 significant singular readings; Papyrus 46 has 471 significant singular readings; Papyrus 47 has 51 significant singular readings; Papyrus 66 has 107 significant singular readings; Papyrus 72 has 98 significant singular readings; Papyrus 75 has 119 significant singular readings. (In a footnote, Royse helpfully defines “significant singular readings” as “those singular readings that remain after exclusion of nonsense-readings and orthographic variants.”)

The existence of these “singular readings” disproves the myth of the tenacity of errors completely. If mistakes were tenacious, then there would be very few singular readings because these mistakes would’ve been passed down to each successive manuscript.

But they weren’t.

These singular readings disappeared, never to be seen again. Presumably, the scribes didn’t keep the errors because they recognized them as errors. This brings us to one of the strongest arguments for the Majority Text theory: that scribes preferred to copy better manuscripts.

Was There a Scribal Preference to Copy Better Manuscripts?

This could be called the “common sense” side of the Majority Text theory. It goes like this:

Please imagine that you were a scribe charged with copying the New Testament. Further, assume you had two manuscripts to choose from when copying. One appears to be of mediocre quality, the other of good quality.

Which text would you copy?

One of the major underpinnings for the Majority Text theory is that scribes will generally choose to copy better manuscripts over worse manuscripts. (Assuming they had multiple manuscripts to choose from.)

I think this makes sense.

It’s what almost anyone would do.

Again, let’s assume you were in charge of copying the New Testament with several manuscripts to choose from, say five. One of them appears to be of poor quality, one of mediocre quality and the remaining three appear to be of decent quality and – a few small variants aside – appear to be in near perfect agreement. Nearly everyone would choose one of the three to copy from. Or perhaps you’d use all three, using the combination to correct the few small variants between them.

And by the way, I do mean “near perfect agreement” even according to Westcott & Hort.

“The [fourth-century] text of Chrysostom and other Syrian [= Byzantine] fathers … [is] substantially identical with the common late text”

“The fundamental text of late extant Greek MSS generally is beyond all question identical with the dominant Antiochian [= Byzantine] … text of the second half of the fourth century… The Antiochian Fathers and the bulk of extant MSS … must have had in the greater number of extant variations a common original either contemporary with or older than our oldest extant MSS”

“Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek: With Notes on Selected Readings” by Westcott & Hort

The (Byzantine) manuscripts from the Medieval period were “substantially identical” and “beyond all question identical” to those known in the “second half of the fourth century”. That’s from the later 300s to the 1400s; that’s 1,100 years (over a millennia) with virtually no change.

This is especially interesting because they also said the “Antiochian” (Byzantine) text was the “dominant” text in the second half of the 4th century (the later 300s).

Further, Westcott and Hort agreed that the “common text” (Byzantine text) had at its root a text that was as old as – or older than – their oldest manuscripts (Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus). Again, the only reason they didn’t give them any weight was because they (incorrectly) believed the Byzantine text was a combination of the Western and Alexandrian Text types.

Again, we now know this isn’t the case.

Eminent scholars such as E. C. Colwell, G. D. Kilpatrick, and Kurt and Barbara Aland maintained, respectively, that “The overwhelming majority of readings,” “almost all variants,” and “practically all the substantive variants in the text of the New Testament” existed before the year 200. Nevertheless the Hortian text has not been overthrown.

Plus, there are papyrus fragments from quite early that contain Byzantine readings, though often mixed with the other text types.

Further, this argument for Scribes choosing better manuscripts has parallels from the Textual Criticism of non-Biblical works too.

It’s true.

Parallels with Textual Criticism of Non-Biblical works

In the Textual Criticism of Homer’s works, we see excellent parallels with the New Testament, even so far as reproducing similar “text types”.

17. A transmissional approach to textual criticism is not unparalleled. The criticism of the Homeric epics proceeds on much the same line. Not only do Homer’s works have more manuscript evidence available than any other piece of classical literature (though far less than that available for the NT), but Homer also is represented by MSS from a wide chronological and geographical range, from the early papyri through the uncials and Byzantine-era minuscules. The parallels to the NT transmissional situation are remarkably similar, since the Homeric texts exist in three forms: one shorter, one longer, and one in-between.

18. The shorter form in Homer is considered to reflect Alexandrian critical know-how and scholarly revision applied to the text; the Alexandrian text of the NT is clearly shorter, has apparent Alexandrian connections, and may well reflect recensional activity.

19. The longer form of the Homeric text is characterized by popular expansion and scribal “improvement”; the NT Western text generally is considered the “uncontrolled popular text” of the second century with similar characteristics.

20. Between these extremes, a “medium” or “vulgate” text exists, which resisted both the popular expansions and the critical revisions; this text continued in much the same form from the early period into the minuscule era. The NT Byzantine Textform reflects a similar continuance from at least the fourth century onward.

21. Yet the conclusions of Homeric scholarship based on a transmissional-historical approach stand in sharp contrast to those of NT eclecticism:

We have to assume that the original … was a medium [= vulgate] text… The longer texts … were gradually shaken out: if there had been … free trade in long, medium, and short copies at all periods, it is hard to see how this process could have commenced. Accordingly the need of accounting for the eventual predominance of the medium text, when the critics are shown to have been incapable of producing it, leads us to assume a medium text or vulgate in existence during the whole time of the hand-transmission of Homer. This consideration … revives the view … that the Homeric vulgate was in existence before the Alexandrian period… [Such] compels us to assume a central, average, or vulgate text.

(Source for this quote is: “Homer: The Origins and the Transmission“, by Thomas W. Allen)

22. Not only is the parallel between NT transmissional history and that of Homer striking, but the same situation exists regarding the works of Hippocrates. Allen notes that “the actual text of Hippocrates in Galen’s day was essentially the same as that of the mediaeval MSS … [just as] the text of [Homer in] the first century B.C. … is the same as that of the tenth-century minuscules.43

23. In both classical and NT traditions there thus seems to be a “scribal continuity” of a basic “standard text” which remained relatively stable, preserved by the unforced action of copyists through the centuries who merely copied faithfully the text which lay before them. Further, such a text appears to prevail in the larger quantity of copies in Homer, Hippocrates, and the NT tradition. Apart from a clear indication that such consensus texts were produced by formal recension, it would appear that normal scribal activity and transmissional continuity would preserve in most manuscripts “not only a very ancient text, but a very pure line of very ancient text.”

Source. (An excellent article by the way, though a bit technical.)

So in the “text types” of Homer, you have:

- Short = Alexandrian, reflecting “scholarly revision”

- Medium = Widely believed to be the most accurate because it maintained a near-identical form across 1000+ years, and most manuscripts are of this type

- Long = characterized by Scribal “improvement” and expansion.

In the New Testament, you have:

- Short = Alexandrian Text type,

- Medium = Byzantine Text type, characterized by near-identical form over 1000+ years, and most manuscripts are of this type

- Long/paraphrase = Western Text type, characterized by its “love of paraphrase” is like the “uncontrolled popular text” of Homer

Among scholars, there’s little doubt that the “medium” text type of Homer is the original, while the short is the result of “scholarly revision”. (The long is discarded because of its poor quality) In the New Testament, it’s the complete opposite, except the discarding of the poor quality of the Western Text. The “medium” Byzantine text with its near-identical form for 1000+ years is ignored, and the shorter Alexandrian text is preferred.

Why?

Why discard a Text Type that remained virtually unchanged for 1000+ years?

It doesn’t make sense (to me).

Notice too, that – in Homer – the shorter Alexandrian “text type” was regarded to be the result of “scholarly revision”. I’m going to re-quote something we looked at earlier.

(Note: The following is regarding the Alexandrian Text type manuscripts.)

However, the antiquity of these manuscripts is no indication of reliability because a prominent church father in Alexandria testified that manuscripts were already corrupt by the third century. Origen, the Alexandrian church father in the early third century, said:

“…the differences among the manuscripts [of the Gospels] have become great, either through the negligence of some copyists or through the perverse audacity of others; they either neglect to check over what they have transcribed, or, in the process of checking, they lengthen or shorten, as they please.

(Bruce Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3rd ed. (1991), pp. 151-152).Origen is of course speaking of the manuscripts of his location, Alexandria, Egypt. By an Alexandrian Church father’s own admission, manuscripts in Alexandria by 200 AD were already corrupt. Irenaeus in the 2nd century, though not in Alexandria, made a similar admission on the state of corruption among New Testament manuscripts. Daniel B. Wallace says, “Revelation was copied less often than any other book of the NT, and yet Irenaeus admits that it was already corrupted — within just a few decades of the writing of the Apocalypse”

As we’ve already seen, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus were certainly of mediocre to poor quality. It has often been stated by Majority Text advocates that “good money pushes out bad“, and the same principle can be applied to Textual Criticism. They believe that – over time – good manuscripts will push out bad manuscripts.

Are scribes more likely to add or subtract?

One of the major arguments against the Majority Text by those who prefer the Critical text is the accusation that scribes added the “extra” content. One of Aland’s rules for Textual Criticism is:

The venerable maxim lectio brevior lectio potior (“the shorter reading is the more probable reading”) is certainly right in many instances. But here again the principle cannot be applied mechanically.

As you may remember, both Aland and Westcott & Hort had trouble sticking to their rules (except “older is better”). They both believed that scribes were more likely to add content than remove content. Therefore, they had the saying “the shorter reading is the more probable reading.”

But is the shorter reading more probable?

There is a well-known error when copying manuscripts by hand called “parablepsis”. (It’s also called “Haplography”, but the two are technically slightly different”) This error occurs when two words or phrases end with the same letters/words, and the scribe accidentally skips everything in between.

For example:

This is our example, but

we’ll need some words so

This is our sample text

You’re copying it down,

but this clause in red is

sadly skipped because

because the next line also

contains the word text

Thus your eye jumps from

the first occurrence of the

word “text” to the second,

and you accidentally skip

everything between them,

which is everything in red.

The scribe’s line of sight skips from the first instance of the word “text” to the second instance of the word “text”, accidentally skipping everything in between (the red text in the example). This is a well-known, well-documented scribal error, even having its own name. You might’ve even made this error yourself, just likely not on New Testament manuscripts. 😉

Further, this can happen in smaller increments too.

The original texts were written in all capital letters and there were no spaces between the words. Therefore, it wouldn’t be hard to skip some intervening letters to drop a word. (Greek words often have similar endings because of the nature of the Greek language.) These errors of parablepsis and haplography are commonly known and well-documented.

These errors alone account for hundreds of differences between the Alexandrian and Byzantine Text types.

Seriously.

As we’ve seen, the Byzantine Text type is significantly longer than the Alexandrian Text type. This accidental skipping could account for a very significant portion of the longer Byzantine Textual Variants. If you’d like to read a longer treatment of this topic, I highly recommend this article.

Further, if you remember from our discussion of Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, this type of omission is recognized in them.

“It should be noted, however, that there is no prominent Biblical MS. in which there occur such gross cases of misspelling, faulty grammar, and omission, as in B [Vaticanus].”

Source: The New Westminster Dictionary of the Bible

And the man who found Codex Sinaiticus (Tischendorf) considered it the greatest find of his life, but he still said:

The New Testament…is extremely unreliable…on many occasions 10, 20, 30, 40, words are dropped…letters, words, even whole sentences are frequently written twice over, or begun and immediately canceled. That gross blunder, whereby a clause is omitted because it happens to end in the same word as the clause preceding, occurs no less than 115 times in the New Testament.

So, is there a Scribal preference to add rather than subtract?

Certainly not in all cases.

There are plenty of Textual Variants between the Alexandrian and Byzantine Text types (where the Alexandrian is shorter) which can’t be explained this way. However, a significant number of variants can be explained by this simple scribal error.

This author is completely unaware of any proof that scribes preferred to add rather than subtract. It has been asserted many times, but it never seems to be accompanied by proof. It might be out there, but I haven’t seen it. (Please send me an email via the contact page if you find some.)

(Additionally and anecdotally, I’ve done a fair bit of copying in my life, and when I’m quoting someone else, I’ve never been tempted to add to the quote because that would be dishonest. It’s not a stretch to imagine that Christian scribes would feel the same, especially about Scripture.)

Now, we’ll look at the arguments against the Majority Text.

Arguments Against the Majority Text

Despite the strong support we’ve just seen, the Majority Text theory does have some significant weaknesses.

One of the greatest supporters of the Critical Text is Daniel Wallace. He wrote a long “rebuttal” of the Majority Text entitled: “The Majority Text and the Original Text: Are They Identical?” That appears to be the standard “go to” article for rebutting the Majority text. James Snapp Jr. wrote a rebuttal to Wallace’s article in four parts. (Part one, part two, part three, part four.)

Majority of What Manuscripts?

The early Christians translated the New Testament into other languages, and we have many of these translations. If you only include the Greek manuscripts, then indeed the Byzantine Text type is the majority. However, the picture changes if you include translations into other languages.

While translations aren’t very useful for deciding the exact wording of Greek, they can be very useful in deciding if certain words, phrases, and/or verses were included.

The translations into other languages are called “versions”, and Dan Wallace said this:

Second, the extant versional manuscripts are virtually triple the extant Greek manuscripts in number (i.e., there are about 15,000 versional manuscripts). The vast majority of them (mostly 10,000 Vulgate copies) do not affirm the Byzantine text. If one wishes to speak about the majority, why restrict the discussion only to extant Greek witnesses and not include the versional witnesses?

Source. – Daniel Wallace

And from another source:

However, it must be noted that the Western church changed languages in the 600’s with the adoption of the Vulgate as its official version. From that point forward, the Roman Catholic Church preferred to keep their manuscript tradition in Latin rather than Greek. In the Vulgate, we find over half of the Alexandrian readings. The Alexandrian text is about 5% smaller than the Byzantine text, and there are some differences in words between the two texts. No Christian doctrine is omitted from the Alexandrian text, but some appear strengthened in the Byzantine text.

So the Majority Text changes very significantly when you include just the other versional manuscripts. (And that’s not including quotes by including the early church fathers). That alone changes things a lot. So if you hold to the Majority Text theory, you’ll need to decide if you’ll only include Greek manuscripts. If so, you’ll need a good reason to exclude the various versions.

One reason could be that “something is always lost in translation”. A poor translation can obscure many things about the original language, making it difficult to know. For example, imagine trying to reconstruct the Greek text by having several different English translations. If you were working from an NASB or NKJV, you might have some luck. But if you’re working from poor translations like the NLT, NIV, or any of the paraphrase translations, you’re basically out of luck.

However, even the worst of these can tell you about the presence or absence of a verse.

Majority at What Time?

Let’s assume – for the sake of argument – that the Majority Text is essentially identical to the original. The question then becomes:

The Majority Text at what time?

If you take the Majority Text theory and apply it to modern times, then there are clearly more copies of the modern Critical Text than the Majority Text. Whether you count Bible translations based on the Critical Text vs Bible translations based on the Majority Text; or copies of the Greek Majority Text vs the Greek Critical Text, the Critical Text becomes the clear winner.

If you backup to the first 500 years of the Church, the Byzantine Text type is in the clear minority of the manuscripts we’ve found. (Though as we’ve already seen there’s reason to think it was the dominant text.)

Disproportionate Copying

The mathematical model for the Byzantine Majority Text relies on an assumption. The assumption is that each manuscript was copied a relatively equal number of times. However, that’s not necessarily the case.

For example, let’s say that three scribes copied from the original, and one of them made an error. But what if a very passionate scribe decided to make a lot of copies… but he was copying from the manuscript with the mistake? It’s easy to see how you could end up with a disproportionate number of copies with errors. It doesn’t mean they will enter the majority, but it’s a possibility.

You might say, “But that wouldn’t happen.”

Actually, we know it did… we just don’t know if it happened with errors.

The fact that the Byzantine Text type dominates the manuscript copies is proof of disproportionate copying. (Or that other manuscripts were destroyed, which we’ll look at more in a minute.)

This disproportionate copying could be a good thing, as we saw in the section on whether scribes copied better manuscripts. However, that doesn’t mean it was a good thing. There’s simply no way to know if the more accurate manuscripts were preserved this way. You would need to trust that scribes did indeed copy the best manuscripts.

Removing Copies from the Stream of Transmission

Further, the Majority Text theory could be in trouble if it could be proven that large chunks of manuscripts were lost. Unfortunately, we know that happened in at least two ways.

Accidental Loss Through Age and Use

The first manuscripts were copied onto either papyrus (ancient paper) or parchment (animal skins). Neither survives through the ages well. That’s why the overwhelming vast majority of our earliest Greek manuscripts come from one of the driest climates on the planet: Egypt. Being so dry, Egypt has an ideal climate for such preservation.

Majority Text advocates will typically argue that the earliest Byzantine manuscripts were lost because no other climate on earth is as favorable for preserving documents as Egypt. Thus, they say there were Byzantine Text-type manuscripts elsewhere, but they didn’t survive because the climate wasn’t as suitable for preservation. That’s definitely possible – maybe even likely – but by no means certain.

Intentional destruction via persecution

A sad fact of history is that when Christians are persecuted, copies of the Bible are usually caught in the crossfire. In fact, it was Roman policy to destroy Biblical manuscripts at one time.

A vast number of early manuscripts were destroyed in the early persecutions of the Church. There were already ten major periods of persecution of Christians before Nicea:

- Persecution under Nero (64-68).

- Persecution under Domitian (90-96).