Since I reference Greek so often on this website, I thought it might be helpful and fun to do a short little primer on how cool the Greek language really is. 🙂 I’ll also include some resources at the end where you can go to learn more.

(Note: the examples below are just that; examples. They are in no way intended to reproduce correct Koine Greek style, grammar, or syntax; they are examples only.)

Let’s Get started

Let’s take a simple sentence:

The kid held the baby.

Here’s a super quick, one-paragraph grammar refresher:

The subject of the sentence is who (or what) the sentence is about. In this case, it’s “the kid”. The “direct object”, is what receives the action of the sentence. In this case, it’s “the baby” because it is what the verb (held) acted on.

This leads us to one of the major differences between Greek and English:

- In English, you decide which word is the subject (or direct object) by the order of the words

- In Greek, you decide which word is the subject (or direct object) by the form of the words

Greek words can take several different forms to indicate their function in the sentence. We (sort of) have this in English too. For example, let’s take the following sentence.

He talked to him.

The order of the words tells you what’s going on. However, the form does also. For example, you would never say:

Him talked to he.

It just sounds completely wrong to our ears. He/him are both 3rd person masculine pronouns, and therefore are basically the same word… almost. The difference is “he” is a subject form; “him” is a direct object form. We know this instinctively – so would never make the mistake – but we are rarely taught why (now you know).

Follow:

- The “stem” (or base) of the word is “h”,

- you add “e” (to get “he“) if it’s the subject;

- you add “im” (to get “him“) if it’s the direct object.

So lets go back to our example sentence, “the kid held the baby”. Now, we’ll add some endings to tell you the different words’ function in the sentence.

- We’ll add “on” if it’s the subject.

- We’ll add “don” if it’s the direct object. (“d” + “on” because it’s the direct object)

So, our example sentence “the kid held the baby” becomes:

The kidon held the babydon.

You could write this sentence several ways, all with the same meaning… because of the endings. Now, in Greek more than just the endings change. But to keep it simple here, we’ll pretend that only the endings of Koine Greek words change for the examples in the rest of this article.

Form = Function

You can change the order of the words to add emphasis. Remember, the endings let the reader know what the word does, so you can change the order for emphasis. For example:

- The babydon held the kidon.

Saying “the baby held the kid” is non-nonsensical in English. However, by adding the endings, we know that (in the above sentence) the kid is doing the holding even though the English word order is wrong. Further, we know the baby was held, even though – again – the word order is wrong in English.

You can move words around and the reader will still understand who’s the subject of the sentence. Like so:

- The babydon held the kidon. (emphasizes the baby – the direct object)

- Held the babydon the kidon. (emphasizes the action, i.e. “holding”)

- The kidon held the babydon. (emphasizes the kid – the subject.)

Fun huh?

(I should add that there are rules for position in Greek, so you know which words go with which other words. That’s beyond the scope of this article though.)

But it gets better

Let’s say we wanted to make it more than one kid holding the baby. In English, we typically add an “s” to make things plural (one kid > many kids). Greek does a similar thing

Remember, in our example here, we added “on” to the end of a word to make it the subject. Let’s make an addition to that rule:

- Add “on” to a word to make it a singular (one) subject

- Add “os” to a word to make it a plural (many) subject

For example:

The kidos held the babydon.

Now, you have multiple kids holding the baby. (Of course, that might be hard if they tried at the same time…) You’ve told the audience not only who is the subject of the sentence, but how many there are… are with a simple two-letter ending.

Pretty neat huh?

A Better way to do Gender?

But now, let’s get even crazier. Let’s say we wanted to tell the reader the gender of the kid. Our English word “kid” is what’s called a “neuter” word. That means it doesn’t tell you whether the kid is a boy or girl. If you wanted to say the kid was male or female in English, you would need to either add another word or change a word. You could say:

- The (male) kid held the baby

- The boy held the baby.

But in Greek, you just need to change the form of the word

Seriously.

Remember, you can tell almost everything about a Greek word by the form of the word. Change the form of the word and you change everything. For example:

- We’ll keep using the “on” ending for a singular (one) neuter (non-gender specific) subject.

- We’ll use “an” for a singular (one) male subject.

- We’ll use “en” for a singular (one) female subject.

- We’ll also do the same with the “don” endings (“dan” = singular male, “den” = singular female, “don” = singular neuter.)

So, check this out.

The kidan held the babydon.

That tells you a single male child held the baby, but doesn’t tell you the baby’s gender.

The kiden held the babydan.

That tells you a single female child held the male baby.

But you can combine them too!

For example, check out this chart.

| Male | Neuter | Female | |

| Singular Endings | "an" (kidan) | "on" (kidon) | "en" (kiden) |

| Plural Endings | "as" (kidas) | "os" (kidos) | "es" (kides) |

You can give a LOT of information by just changing a few letters around… and this works for the direct object too. Remember, we added a “d” before our endings to indicate it’s the direct object. As long as we have the “d”, we know it’s the direct object even when you change the “on” endings.

For example:

The kiden held the babydes. (one female kid held multiple female babies.)

The kidas held the babydos. (multiple male kids held more than one baby; but the genders of the babies aren’t specified because of the “neuter” ending.)

A good “article”

In Greek, you can use the definite article (“the” in English) to replace a pronoun (he/she/it/them/they). To do that, you just use the appropriate endings on the definite article (“the” in English).

For example:

Theas punched thedan.

Literally “the punched the”, which would be gibberish in English. But – because of the endings – that would be a perfectly legitimate sentence in Greek. It means: “the males punched the male”. It would probably be considered poor writing though.

However, we don’t know anything else about them because “the” doesn’t give more information. It might makes sense as part of a larger unit though; i.e. with more sentences around it. (for example “The old men snuck up on the robber. Theas punched thedan.”)

Greek Participles

Both English and Greek have participles, which are words that can function as both a verb and an adjective. Adjectives describe nouns, for example: “The golden trophy”; golden is an adjective that tells us something about the trophy (namely color). Trophy is a the noun, which is being described by the adjective.

Now unlike “golden”, some words can be verbs or adjectives depending on usage. For example, the English word “running” can be either a verb or an adjective:

- Verb: “The man is running

- Adjective: “That’s a running trophy”

The cool thing about Greek participles is that they have number, gender, and case just like nouns! Now to identify that it’s a participle, we’ll do the same as we did with the direct object above. For for the neuter singular, it would be:

- “on” if it’s the subject.

- “don” if it’s the direct object.

- “pon” if it’s a participle (“p” + “on” because it’s a participle)

For example:

Heldpon

Tells us that one person held something, but doesn’t tell us the gender of the person. However, we can convey gender with Greek participles. For example:

Heldpan = one male is holding something

Heldpes = multiple females are holding something

When you see a masculine participle functioning as a verb in Greek, it means a male is doing something. (or are having something done to them in the passive voice.) Likewise, feminine participles mean females are doing something. (or are having something done to them in the passive voice.)

Non-participle verbs in Greek don’t convey gender, but do convey other things. If you want to know more about Greek, check out the resources at the end.

Conclusion

There’s more I could explain, but I wanted to keep this short and fun. Enjoy knowing more about Koine Greek than 90% of Christians… just don’t try to use my hypothetical endings to read real Koine Greek. I made them up and they have no meaning outside the examples in this article.

If you want to learn more about Biblical (Koine) Greek, here are a few resources:

- TFBI Grammatical and Morphological Manual with Answers (A good intro PDF with a very complete overview. Read this first, especially the introduction.)

- Ezra Project Grammar study on noun and verb types/forms (Good overview for them, read this next)

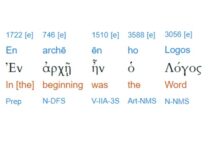

- Biblehub.com Interlinear. Once you understand the forms and know the Biblehub parsing guide, their interlinear is a window into Greek without needing to memorize all the word forms. It’s much better on a computer, as hovering your mouse over the parsing beneath a word will reveal the form of the word.

- Learn Ancient Greek, with Prof. Leonard Muellner – The Center for Hellenic Studies (A YouTube playlist which covers much of the material in the first semesters of a Greek course.)

Enjoy!

Your Greek article made me appreciate the olde English of the KJV…with the thine-thou-singular and the ye-plural

Agreed, it’s a shame that modern English has lost some of those features.

Thanks. Your articles on Koine and Greek Biblical translations have been very helpful to me. There’s something I hope you can help me with: the Greek word ἐγώ, according to Strong’s (G1473) etymology, is 1st person singular pronoun. Yet, it’s often translated into English as 1st person plural pronoun, as in Mt 2:23 and Mt 6:9-13. I would appreciate any enlightenment you can give me on this. Thanks!

To use English as an example, we don’t have separate diction entries for “car” and “cars”, so they don’t in Greek lexicons either. To use the example from the article, “kidan” and “kidas” wouldn’t have separate dictionary entries just for the difference between singular and plural. The dictionary definition must pick a form of the word to use, and that’s the one they picked. That’s really it. In fact, ἐγώ has eleven forms that are used in the NT to indicate singular vs plural and the function in the sentence.

ἡμᾶς — 167 occurrences

ἡμεῖς — 127 occurrences

ἡμῖν — 169 occurrences

ἡμῶν — 408 occurrences

ἐγὼ — 352 occurrences

ἐμὲ — 90 occurrences

ἐμοὶ — 93 occurrences

ἐμοῦ — 109 occurrences

με — 293 occurrences

μοι — 225 occurrences

μου — 567 occurrences