This article is an introduction that will cover a few foundational basics of Biblical/Koine Greek in English only. I won’t use Greek words or letters in the explanations in this article, so you’ll be able to follow along using English exclusively.

This article is an introduction that will cover a few foundational basics of Biblical/Koine Greek in English only. I won’t use Greek words or letters in the explanations in this article, so you’ll be able to follow along using English exclusively.

Now, while I’ll be using English to explain Greek grammar, I’m not intending to actually teach Greek. That’s not my goal here. My goal here is a overview of the Greek language. It’s like the difference between describing how a car works and actually building one. I’ll be describing how the car works, not teaching you to build one.

Further: Assume that everything I say about Greek in this article will have exceptions.

Everything.

Again, I’m intending to create an overview/introduction to Greek, not to teach Greek. If you actually want to learn Greek, I suggest a Greek course.

That said, let’s begin.

Inflections

As mentioned in another article, A major difference between English and Greek is this:

- In English, we make sense of a sentence primarily based on word order (though word form matters a bit too)

- In Greek, you primarily make sense of a sentence based on word form (though word order matters a bit too)

Greek words can take several different forms to indicate their function in the sentence. We (sort of) have this in English too. For example, let’s take the following sentence.

He talked to him.

The order of the words tells you what’s going on. However, the form does also. For example, you would never say:

Him talked to he.

It just sounds completely wrong to our ears. He/him are both 3rd person masculine pronouns, and therefore are basically the same word… almost. The difference is “he” is the subject form while “him” is the direct object form. We know this instinctively so would never make the mistake, but we are rarely taught why (now you know).

In English, changing the word order to “Him talked to he” doesn’t work because we make sense of a sentence via the word order. However, in Greek you know what a word does by it’s form, not its position in a sentence. Thus, that example sentence above would make perfect sense in Greek because the form of the word tells you what the word does.

You could actually write that sentence in Greek like this:

Him he talked.

And it would make perfect sense in Greek because of the form of the words. Again, the form of the word is much more important in Greek than the word’s position in a sentence. Now that you understand that basic concept, we’ll get into what the forms do; starting with nouns and adjectives.

Nouns and Adjectives

Here’s a quick refresher for those who hated grammar in school: (Ironically, that includes me; how times have changed.)

- A noun is a person, place, or thing. (For example “the car“)

- An adjective describes a noun. (For example: “the red car”; the adjective tells you something about the noun.)

In Greek, nouns and adjectives have three elements that are determined by the word’s form:

- Case (indicates the word’s function in the sentence)

- Gender (indicates if the word is masculine, feminine, or neuter)

- Number (indicates if the word is singular or plural)

We’ll be using a type of shorthand to indicate these features, which will consist of the word, then a dash “-“, and then three capital letters. Common examples might look like this:

- car-NMS

- car-AFP

- car-DNS

There are other letters, but that’ll give you an example. The first letter will indicate “case”, the second letter will indicate grammatical gender, and the third will indicate number. I chose those these specific abbreviations for a good reason, and I think you’ll be happy I did when I reveal why later in the article.

We’ll start with cases first.

Grammatical cases

These cases apply to Greek nouns, adjectives, and participles, but we’ll ignore participles for now. The grammatical case of a noun or adjective tells you a lot about the word’s function in a sentence. Here’s a super short overview of the five grammatical cases, and we’ll go into each case in more depth under that case’s section:

- Vocative case (Used to indicate direct address)

- Nominative case (Used to indicate the subject of the sentence)

- Accusative case (Used primarily to indicate objects in a sentence, especially direct objects)

- Dative Case (Used primarily to indicate indirect objects in a sentence, but has other uses)

- Genitive case (Used to indicate word association)

Don’t try to memorize those now because we’ll go through them one-by-one. We’ll start with the vocative case because it’s simple and easy to understand.

Vocative Case

A noun in the vocative case indicates direct address. That is, the noun (usually a person) is being addressed. For example:

“John (vocative case), come here.”

John is being addressed, and thus you would put “John” in the Greek vocative case. However, many Greek nouns use the exact same form for the vocative case and the nominative case. Thus, the Vocative and Nominative cases are identical for many Greek nouns.

And that’s it for the vocative case.

I told you it was simple. 🙂

To indicate the vocative case in this article, the letter “V” will be added to a noun after a dash. For example, the noun “John” in the vocative case would look like this: “John-VMS”, (The “MS” indicates masculine and singular.)

However, don’t forget that an “N” in that first position could also be the vocative with many words. (Again, because the vocative and nominative cases are the same for many words)

Now we’ll move onto the Nominative case, which is also fairly simple.

Nominative case

The nominative case is essentially the “subject case”. A Koine Greek noun that’s in the nominative case is the subject of the sentence (what it’s about) which almost universally means the subject of the verb. That is the subject/nominative case noun either does the action (with an active or middle verb) or receives the action of the verb (with a passive verb).

For example:

John (Nominative case) drove the car. (active verb)

John (Nominative case) was given a gift. (passive verb)

To indicate the Nominative case, the letter “N” will be added to a noun after a dash. For example, the noun “John” in the nominative case would look like this: “John-NMS”, (The “MS” indicates masculine and singular.)

John-NMS drove the car.

The “N” in “NMS” tells you that John is in the nominative case, and thus is the subject of the sentence. Now we’ll move to the accusative case.

Accusative Case

One of the most common uses of the accusative case is as the direct object. (We’ll cover the 2 other common uses in a moment. ) That is, the thing that receives the action of an active verb. (The subject receives the action of a passive verb, covered later under verbs) For example:

John drove the car.

The car received the action of the verb “drove”, and thus it would be in the accusative case because it’s the direct object (the thing that receives the action of the verb).

To indicate the Accusative case, the letter “A” will be added to a noun after a dash. For example, the noun “car” would look like this: “car-ANS”, (The “NS” indicates neuter and singular.)

The accusative can also be used to indicate something directly related to the direct object. For example:

John drove the car-ANS many miles–ANS.

“Miles” is directly and closely related to “drove”, and thus it’s also in the accusative case.

The last common usage of the Accusative is also as an object; specifically the object of a preposition. We’ll cover prepositions lower down, so don’t worry about them now. If you want a quick refresher course, here’s an article on prepositional phrases. As an example, the word “in” is a preposition.

John was in the store-ANS.

“In the store” is a prepositional phrase. “In” is the preposition, and “store” is the object of the preposition, thus “store” would be in the accusative case. This will make more sense when we go through prepositions later.

Dative Case

For the purposes of this article, I will grossly oversimplify and say that the Dative case is the case of the indirect object. Indirect objects are affected by the verb, but not directly. For example:

John drove the car to Mary (Dative case).

John drove the car for Mary (Dative case).

“Mary” is the indirect object, and you can tell because “Mary” was indirectly affected by the verb. The verb “drove” directly affects the direct object (car), but indirectly affects the indirect object (Mary). It usually tells us who/what the action was done for; it can also tell us “to whom” an action was done.

To indicate the Dative case, the letter “D” will be added to a noun after a dash. For example, the noun “Mary” would look like this: “Mary-DFS”, (The “FS” indicates feminine and singular.)

The Dative case can also be used to denote instrumentality; i.e. the means through which it was done, or how it was done.

John threw the rock with his arm-DNS

The Dative case can also tell us the “location” of something, or the “sphere” in which it’s done. For example:

John stayed at home-DNS

Genitive Case

The Genitive case doesn’t have a good parallel in English. The genitive case indicates a word is associated with another word. The closest parallel in English would be possession by adding an apostrophe + “s” to the end of the a word. For example:

John‘s house

In Greek, the genitive case is used to show that the word in the genitive case is associated with another word. However, it’s works the opposite of English. Where in English you add the apostrophe + “s” to the word that “owns” the other word (“John’s” in the example just above), in Greek you put the word that is “owned” (“house” in the example above) in the genitive case.

To indicate the genitive case, the letter “G” will be added to a noun after a dash. For example, the noun “house” would look like this: “house-GNS”, (The “NS” indicates neuter and singular.)

To return to our example:

John house-GNS

Now, writing “John house” in English makes very little sense. However, in Greek with “house” in the genitive case, you can see that “house” is associated with John; in this case by possession. (John owns the house.) Possession — as in the example above — is one use, though there are others.

One example is descriptive. For example.

A house wood-GNS

That makes no sense… until you realize that the genitive case means the word “wood” is associated with another word, in this case “house”. (Greek genitives usually come after the word they modify) Since “wood” is associated with “house” via the genitive case, it means “a house of wood”. The genitive case is the default case for marking a dependent relationship between two nouns.

That’s it’s primary function.

It does it in many ways, and can indicate many types of relationships, but it’s primary use is to indicate a relationship between two nouns.

Here’s another example that might seem confusing at first.

John was a witness accident-GNS.

You’d translate this as “John was a witness [of the] accident”. The genitive case indicates attachment to the previous noun here, and it’s not Dative since “accident” isn’t affected by the verb. It’s genitive because there’s a relationship between accident and witness; What type of witness? A witness of the accident.

In most cases, you can translate the genitive properly by adding “of”, or “of the” before it. Not in every case, but very often that’s the correct sense. There are more uses for the genitive, but that’ll do for this article/overview.

Next we’ll move on to number and gender, both of which are far more simple because we have them in English.

Nouns and Adjectives: Gender

Gender in Greek is both easier and harder than in English, but mostly the same for the purposes of this article.

All Greek nouns have gender.

Greek has three grammatical genders:

- Masculine

- Neuter

- Feminine

Now, some Greek nouns are of fixed gender and can only be that gender.

For example, the Greek word that means “ring” is a masculine noun. It’s never neuter, it’s never feminine; it’s always masculine. However, rings obviously aren’t biologically male. This is actually similar to languages like Spanish and French. For example, the Spanish word for “book” is “libro”, and it’s masculine.

We sort of have this in English too. For example, “steward” is masculine and never feminine, while “stewardess” is feminine and never masculine. Likewise father/mother/parent are masculine/feminine/neuter forms meaning someone who has had a child. However, we don’t have things like “ring” being masculine.

Some Greek nouns (like many pronouns) can be whatever gender is appropriate for the sentence.

Greek adjectives can always be any gender.

We’ll indicate gender in this article by adding “M” for masculine, “N” for neuter, or “F” for feminine after the letter indicating the grammatical case. So for example:

Son-NMS

Child-NNS

Daughter-NFS

Now that’s covered, we’ll move onto number.

Nouns and Adjectives: Number

This is pretty darn simple since it’s the same in Greek as in English. Singular indicates one, plural indicates more than one. (There’s also a “dual” form for natural pairs like two eyes, two ears, etc. But if I recall correctly it’s not used in the Bible, so it’s irrelevant for this article.)

We’ll indicate number with an “S” for singular or a “P” for plural after the gender; like so:

Child-NMS

Child-NMP (which would translate to “children” since it’s plural.)

This is essentially identical to English, so we’ll move on.

Associating Adjectives with Nouns

Adjectives modify nouns in both English and Greek. However, you must know which adjectives modify which nouns. In Greek, there are two requirements that an adjective must meet before it can modify a noun.

- The adjective must match case, gender, and number with the noun it modifies. Always.

- The adjective must be in what’s called an “attributive position“

#1 is pretty simple, but #2 needs some explanation. In both English and Greek, the adjective must be in what is called an “attributive position” in order to modify a noun. Here’s an example in English:

The red car.

“Red” is an adjective modifying “car”. However, if we move the word “red” it will no longer modify the word “car”. For example:

The car red.

Red the car.

Yes those two examples are a bit nonsensical, but “red” clearly isn’t modifying the word “car” anymore because it’s in the wrong place to do so; it’s not in an “attributive position”.

Greek also has “attributive positions” that an adjective must be in to modify a noun, and Greek has three of them. However, before we can talk about them we need to talk about the Greek definite article (“the” in English) and it’s “grouping function”.

The Greek Definite Article: Grouping Function

First, the Greek definite article has case, gender, and number like nouns and adjectives , so we’ll mark it the same way in this article. For example: “the-NMS”

The Greek definite article (“the” in English), has a LOT of functions in Greek, unlike in English. In English, the word “the” primarily determines if something is definite or not. For example:

- A book (non-definite, could be any book)

- The book (definite; it’s a specific book, usually decided by context.)

In Greek, one of the primary functions of the definite article is to group words together.

Yes, this is VERY different than English.

To show you just how different, I’m going to show you how the definite article can be used to indicate possession. In order to do this, I’m going to write a phrase that translates to “the brother’s cars” (or more literally “the cars of the brother”) with the Greek word order, both with and without the case/gender/number stems added, and with coloring so you can see the grouping more easily.

- the the brother cars

- (the-NMP) (the-GMS) (brother-GMS) (cars-NMP)

Notice that the first occurrence of “the” is “NMP” (Nominative Masculine Plural) and matches the NMP noun (“cars“), while the second is GMS and matches the GMS noun (“brother“).

The NMP article and the NMP noun surround the GMS (Genitive Masculine Singular) article and GMS noun. The NMP article matches with the NMP noun and thus “groups” all the words in-between them together into a single unit = “the brother’s cars”. Remember that genitive indicates a relationship between two nouns, and again the definite article is used to “group” the words together.

Again, this is very different than English.

Further, this is a natural way to say “the brother’s cars” in Koine Greek. It would be normal and clear. However, you could also do it the following ways in Greek: (remember the genitive case’s function here!)

- (the-NMP) (cars-NMP) (the-GMS) (brother-GMS)

- (the-NMP) (cars-NMP) (the-NMP) (the-GMS) (brother-GMS)

Again, all of these would translate to “the brother’s cars” (or more literally “the cars of the brother”). Yes, Greek is quite different in some ways.

The Greek Definite Article: Associating Adjectives with Nouns

Part of the grouping function of the Greek definite article is to associate adjectives with nouns.

That is, you actually need a definite article (“the” in English) in order to even use an adjective! The definite article “groups” things together so you know what goes with what, though not necessarily in the same way/order of the possession example above. In a moment, we’ll look at the three ways the article “groups” things so an adjective ends up in an “attributive position”.

First, don’t forget that an adjective must match case, gender, and number with the noun it’s modifying.

With that in mind (and omitting the case/gender/number suffixes because we’ll assume they’re all the same), here are the three Greek attributive positions using English words:

- The red car

- The car the red (similar to one of the possession examples above)

- car the red (this format is rare though)

All three of these phrases mean “the red car” though we’ll ignore #3 because it’s rare. Now, the following formats would not mean “the red car” because “red isn’t in an attributive position.

- Red the car

- The car red

Those two phrases would mean “the car [is] red”. (Greek likes to assume the word “is”, and often leaves it out.)

Why don’t those two mean “the red car”? Because of the definite article and its grouping function. The Greek definite article both includes and excludes words depending on where it is, but we won’t get bogged down by the details here. Just remember these three Greek attributive position formats:

- The red car

- The car the red

- car the red (this format is rare though)

Again, in order for an adjective to modify a noun, it must be BOTH of these things:

- The adjective must match case, gender, and number with the noun. Always.

- The adjective must be in an attributive position.

If an adjective meets both of those two criteria, then it modifies a noun. Now, I want to show you how nuts this can get, so I’m going to use an example from the Bible, Jude 1:3. I’ll quote the verse below with the part we’ll examine highlighted.

Jude 1:3 (my translation)

Beloved, using all diligent zeal to write to you concerning our common salvation, I had a compulsion to write to you, encouraging you to earnestly contend for the faith which was once for all handed down to the saints.

Now, I’ll post the translation of the words below in the original word order, using parenthesis () to mark the six individual Greek words. To make this easier to see, I’ll also color code the opening article and closing noun in red, the adjectives in blue, and the adverb in green.

(the-DFS) (once for all) (which was handed down-DFS) (the-DMP) (saints-DMP) (faith-DFS).

Yes, that’s how it’s written in Greek. The opening definite article groups everything between it and the noun it matches (faith) into a single unit. Notice, you can have a lot of adjectives in a row before getting to the noun. (Also, that first adjective is also a verb; a participle. More on that later.)

(Note: sometimes the Biblical writers will omit an article even when using an adjective. No idea why, but it does occasionally happen, especially in Mark. However, the case/gender/number rules are fortunately inviolable.)

The Greek Definite Article: Pronoun function

While we’re on the topic of definite articles, we should talk about one function the definite article has in Greek that it doesn’t have in English. In Koine Greek, the definite article can function as a pronoun. A pronoun takes the place of a person, place or thing in a sentence. For example:

- He/him

- She/her

- They/them

You can use the Greek definite article as a pronoun by putting it in the proper case, gender, and number. For example.

John hit Tom in front of the-GFS

That’s literally

John hit Tom in front of the.

Since “the” is singular and feminine, you could translate it “her”.

John hit Tom in front of her.

That’s an example of using the definite article as a pronoun. You could also translate it “the female” since it’s feminine, or “the male” if it was masculine. However, “the woman” or “the man” is generally going to sound more correct in English and isn’t less accurate. (Unless the context dictates “the girl” or “the boy”, or something else.)

There’s an example like the one above in Matthew 1:6. In the translation below, I’ve greyed out and lined through the italicized word which was added for clarity.

Matthew 1:6 (my translation)

And Jesse fathered David the king. And David fathered Solomon from the-GFS

widowof Uriah.

There’s no pronoun there, just the definite article. It literally reads:

“And David fathered Solomon from the-GFS the-GMS Uriah-GMS“.

That’s one Biblical example, but there are others. In fact, depending on how you count the proper translation of participles (covered lower down), using the definite article as a pronoun is one of the most common ways of using definite the article. We’ll discuss this more when we talk about how to translate participles.

Adjectives as Substantives

This section will be short because we do this in English too. Sometimes you can use an adjective by itself without a noun. For example:

- The righteous

- The wicked

- The blind

- The lame

All of the highlighted words are adjectives, and thus normally describe a noun. However, they don’t have to describe a noun. Sometimes they are used on their own like that. Greek does this the same way as English does; the exact same way, so there’s nothing to teach; I just needed to mention it.

Now, it’s important that the gender of substantial adjectives corelates with the gender of the people the adjective is describing. (when it’s describing a person.)

So when you see a masculine substantive (NMS for example) it’s referring to males. This is very important to some passages, and often overlooked since English can’t express gender as often as Greek does.

Nouns and Adjectives Conclusion

There’s more to say, especially about participles, but not yet. We’ll talk more about them later. For now, we’ll move on to verbs.

Koine Greek Verbs

Like English verbs, Koine Greek verbs indicate action or being/existence (was/is etc.). However, Greek verbs convey more information than English verbs do with a single word. In Greek, verbs have five elements that are determined by the word’s form:

- Aspect (Indicates the level of completeness for the action, and can also indicate tense)

- Mood (indicates the level of certainty about the action)

- Voice (indicates whether the subject did the action or received the action)

- Number (indicates if one person or multiple people did the action, or in the passive voice received the action)

- Person (indicates 1st person, 2nd person, or 3rd person)

Greek infinitives and participles (both explained later) have different elements, but we’ll get to that later. For now we’ll walk through each one of these things, starting with mood.

Note: We’re going to look at this “out of order”. Our abbreviations for verbs will look like this: (for example) “-ASM-3S”, but we’ll look at the second part first (“S” in that example).

Why?

Because it’ll be much easier to understand the first part (“A” in that example) once you understand the second part (“S” in that example). Thus, instead of looking at verbal aspect first, we’re going to look at verbal mood first.

Verbal Mood

In Greek, verbal moods primarily indicate the level of certainty about an action. That is, how certain the reader is that the action occurred. We have this same function in English, so this should be easy to learn.

The Indicative Mood

This will be easy because we also have the indicative mood in English and it functions exactly the same way. The indicative mood indicates a statement of fact; the action in question definitely happened. For example:

He will go (indicative) to the store.

He is going (indicative) to the store

He went (indicative) to the store

Grammatically, these events definitely occurred. They are statements of fact, and there’s no possibility that they didn’t happen. Period. They definitely happened.

The Greek indicative mood is the same.

Simple right?

We’ll indicate the indicative mood with a capital “I” as the second letter in our abbreviation, like so: “-AIM-3S”

The Subjunctive Mood

English also has the subjunctive mood, and it functions much the same as it does in Greek. The subjunctive mood indicates the possibility that an event happened, but not the certainty. It “might” happen, but it might not. There’s potential, but not certainty.

For example:

He might go (subjunctive) to the store.

He might be going (subjunctive) to the store

He might have gone (subjunctive) to the store

This one of the primary functions of the subjunctive mood: to indicate the possibility or potential of an action. Because of this, you use the subjunctive for “if” statements in Koine Greek. Note that the second part of an “if” statement is usually (but not always) in the indicative mood. For example:

If he goes (subjunctive) to the store, she will make (indicative) dinner.

Again, this is because the subjunctive indicates the possibility of an action, but doesn’t guarantee that action.

(Pop quiz: in the sentence example just above; what grammatical case should the words “store” and “dinner” be in? Hint: both words should be the same grammatical case.)

The subjunctive mood can also indicate what someone “should” do.

For example:

You should go (subjunctive) to the store.

Notice that “should” isn’t quite an order, but it’s definitely “order-adjacent”. This is called a “hortatory subjunctive”, and we have this in English too with our word “should”. However, while in Greek they use the same form for “might” and “should”, we use the two different words. Thus, you must look at the context of the sentence to decide if “might” or “should” is an appropriate translation. Usually it’s reasonably obvious.

Those are the primary functions of the subjunctive mood. We’ll indicate the subjunctive mood with a capital “S” as the second letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-ASM-3S”

The Optative Mood

The optative mood is pretty rare in the New Testament, but it does occur occasionally. In the NT, it primarily expresses a hope or wish for something. Paul’s many “May it never be!” statements use the optative mood. Here’s an easy example

“May you be blessed (optative) by God!”

That example is the primary way it’s used in the New Testament.

It’s other function isn’t used in the New Testament if I recall correctly, so you can safely ignore it. Therefore, you can focus on the wish/desire aspect (i.e. “may you be blessed by God”) which is how it’s used in the NT.

We’ll indicate the optative mood with a capital “O” as the second letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-AOM-3S”

The Imperative Mood

This one is easy, since we have it in English and it mostly works the same way in Greek. In Greek, the Imperative mood is used for commands, and also for requests. For example:

Leave (imperative) this place.

That’s it’s primary function, but it’s also used for requests too. For example:

Lord, teach (imperative) us to pray

That’s really about it for the imperative mood. It’s a command or request, and that’s about it. Since we already used the letter “I” for Indicative, we’ll indicate the Imperative mood with a capital “M” – for imperative – as the second letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-AMA-3S”

Participles

We have participles in English, and they are the same conceptually in English as they are in Koine Greek. Participles are verb forms that can also function as an adjective; that is, the same word form can be used as either an adjective or a verb. For example:

He is running. (verbal use, indicating an action)

That’s a running trophy. (Adjectival use, since “running” here describes the trophy; it’s a “running trophy”, as opposed to some other type of trophy.)

Koine Greek absolutely adores participles.

Seriously; it loves them.

They’re all over the place, far more than in English.

More importantly, since Greek participles can be used as adjectives, they also have case, gender, and number like adjectives do. Yeah, they’re weird. Normally, Greek verbs have 5 properties:

- Aspect

- Mood

- Voice

- Plurality

- Person

However, Greek participles lose the last two, but then gain three more since they are adjectives. (Though, number and plurality are basically the same.) So like verbs, participles have:

- Aspect

- Mood

- Voice

And like nouns and adjectives they also have:

- Case

- Gender

- Number

So yes, participles are weird. There’s a lot to say about them, but we’ll leave it here for now and come back to participles at the end of the verb section, because they’re… interesting to translate.

We’ll indicate participles with a capital “P” as the second letter in our abbreviation, and notice the addition of case, gender, and number, like so: (for example) “-APA-NMS”.

Infinitives

In both Greek and English, infinitives are verbs being used as nouns. Yes you read that right, for example:

To live (infinitive) is a great adventure

The subject of the sentence is a verbal action “to live”, but there’s no actual action happening. Thus, the verb – an infinitive – is functioning as a noun. In English, infinitives usually have the word “to” in front of them. i.e. “to live”, “to fight”, “to buy”, etc. There are exceptions to this in English, but they aren’t common and we won’t deal with them here. (This article does though if you’re curious.)

Normally, Greek verbs have 5 properties:

- Aspect

- Mood

- Voice

- Plurality

- Person

However, Greek infinitives lack plurality and person and only have the first 3: aspect, mood, and voice. Mostly, they function in Greek in the same way they function in English, which makes things easy.

Since we already used the letter “I” for Indicative, we’ll indicate Infinitives with a capital “N” – for infinitive – as the second letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-ANA”. Again, note the lack of the plurality and person, signified by the lack of the “3S” in the example.

Greek Moods Conclusion

Here’s a quick recap:

- The Indicative mood (example: “-AIA-3S”) This is a statement of fact; the action in question definitely happened.

- The Subjunctive Mood (example: “-ASA-3S”) This is a statement of possibility, it “might” happen or “should” happen, but that doesn’t mean it will. Also used in “if” statements.

- The Optative Mood (example: “-AOA-3S”) In the New Testament, this indicates a wish, hope or desire for something to happen: “May it be so!”

- The Imperative Mood (example: “-AMA-3S”) This expresses a command or request. “Leave here now!”, or “Teach us something?”

- Participles (example: “-APA-NMS”) Participles are verbs that can also function as adjectives, and thus they also have case, gender, and number.

- Infinitives (example: “-ANA”) These are verbs being used as nouns.

Now that we have a firm grasp of Koine Greek verbal moods, we’ll back up and learn about verbal aspect.

Verbal Aspect

Important: nearly everyone else will say “tense” instead of “aspect” to teach Greek verbs. However, I’m using “aspect” intentionally because I don’t want you thinking this primarily refers to time/tense.

Aspect doesn’t necessarily mean tense in Greek. (even though it’s talked about that way sometimes for reasons which will become obvious.)

To be clear, it’s not wrong to think of verbal aspect like verbal tense in some cases. That’s why so many do it. However, I personally found it very helpful to think of “aspect” instead of “tense” because it helped me think more like a native Greek speaker would think.

Thus, I’m doing the same for you here.

In Greek, verbs are more concerned with the type of action (completed vs ongoing) than when the action took place. In English, it’s almost the opposite. Our verbs have “tense” to tell us when the action took place, but we add other words to tell us about the type of action.

Again, Greek primarily cares about the type of action, not when the action took place. It obviously can express time too, but not as a primary function.

This will become more clear as we dive into the different Greek verbal aspects.

The Aorist Aspect

the Aorist aspect indicates an action that is complete. It’s done, finished. You can think of it like a picture capturing a snapshot in time. Once the picture was taken, the action is complete. When you see Aorist, think “completed action”.

The Aorist aspect tells you that an action is complete, but does not tell you when that action occurred. (except in the indicative mood.)

Another way to look at it is to pretend that you are above/outside the action looking at the whole action at once. That is, you see the action in it’s entirety all at once, regardless of when that action took place. (Yes it’s a strange concept for English readers since we don’t really have anything quite like that.)

It’s like if you could be above a battlefield and take a picture that somehow shows the entire battle at once. I’m not talking about a video though; it would be like if you could somehow take a picture that showed the entire battle in a single picture. One picture that showed everything, regardless of the time in which it took place.

That’s the aorist aspect: completed action, or an action that’s viewed in its entirety all at once.

Now, the aorist in the indicative mood indicates simple past tense action.

In other moods it’s doesn’t, but in the indicative mood it does. So when you see the aorist indicative, it’s simple past tense. However, that’s only true in the indicative mood. For example:

He fought (aorist indicative) the good fight.

Simple past tense, expressing a completed action in the past. However – and I can’t stress this enough – Aorist does not simply mean “past tense”; there’s more to it than that. It can include the past tense – and often does – but don’t think it always means the past tense, because it doesn’t.

We’ll indicate the Aroist aspect with a capital “A” as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-AIM-3S”

The Present Aspect

Let’s get the not-so-obvious out of the way first. Despite the name, the Greek present aspect does not simply mean “present tense”; it only means “present tense” in the indicative mood. thus, when you hear someone say “it’s in the Greek present tense”, don’t assume that’s the same as the English present tense unless it’s also in the indicative mood.

That’s important.

Very important.

Much like the aorist doesn’t simply mean past tense, the present aspect doesn’t simply mean present tense.

We said that the aorist aspect is like a snapshot of a battle where you can somehow ‘magically’ see the entire battle in a single photograph. However, the present aspect is in some ways the opposite of the aorist aspect. The present aspect is like you are “present” watching the events unfold in real time. It like watching a video of an event that’s unfolding. This isn’t a one-time thing; it’s continual, ongoing action. It’s always happening, or sometimes happening continually.

That’s the essence of the present tense: ongoing/in process/continual action.

Going (present aspect) on his way.

When was he going? No idea. In fact, you could tack past, present, or future onto that and they would all make sense.

He was going on his way.

He is going on his way.

He will be going on his way.

When did it happen? Again we have no idea. However, we do know that “going” is an “in process” action. It happening continually and/or ongoing. This is a great example of the Greek present aspect because it could be happening at any time, but we do know the action in ongoing.

In the indicative mood, the present aspect does indicate the present tense.

There are two English forms that are used to show this: simple present tense, and the present progressive tense. For example:

He grows flowers (English’s simple present tense.)

He is growing flowers (English’s present progressive tense.)

This tells us that not only the the action is ongoing, but the indicative mood tells us that it’s happening right now. Greek uses the present aspect both of these ways, so context will tell you what’s intended. (Hint: if you translate as one and it sounds weird, try the other.)

We’ll indicate the present aspect with a capital “P” as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIM-3S”

The Imperfect Aspect

This one is fairly simple for several reasons. Reason #1: the Greek imperfect aspect only occurs in the indicative mood, and no other moods. (no subjunctive, imperative, etc.) Reason #2: it’s simple to explain. The Imperfect aspect indicates an action in the past that was ongoing.

It’s pretty simple, for example:

The boys were fighting (imperfect) until they were separated.

In some ways it’s like the present aspect (ongoing action) only the events are happening in the past. This also makes it simple to translate in many cases. You use a past tense verb of being (was/were) plus a verb ending in “ing”. So, “He was fighting”, “they were fighting”, “She was nursing”, “they were growing”, etc.

It’s also sometimes used by a verb of being: i.e. “was”, but was in the sense of “continually was”. So in Matthew 3:4, it says that John the Baptizer’s food was (imperfect aspect) locusts and wild honey. That means his food was continually locusts and wild honey. Usually in these cases it’s translated simply as “was” because most other translation would sound really awkward in English.

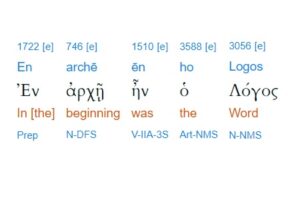

Fun note: the various “was” words in the opening of John’s Gospel are in the imperfect tense. So the Word’s (Jesus’s) existence was ongoing and continual, not one-time; He “was existing”. Pretty cool huh? 🙂

We’ll indicate the imperfect aspect with a capital “I” as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-IIM-3S”

The Perfect Aspect

The perfect aspect combines two ideas into one. It refers to an action that (1) was completed in the past, and (2) has effects that remain until the present moment. Notice the two features: completed action in the past, plus ongoing effects (or more commonly an ongoing state) in the present. For example:

The nuclear bomb has irradiated (perfect tense) the area

Notice the dual focus. The bomb completed its action of irradiating the area in the past, but then that state of being irradiated continues up until this present moment. This is usually translated with the word has/have, depending on if it’s singular or plural.

For example:

The nuclear bomb has irradiated the area. (perfect tense, singular and active)

The nuclear bombs have irradiated the area. (perfect tense, plural and active)

The area has been irradiated by the nuclear bombs. (perfect tense, singular and passive)

The areas have been irradiated by the nuclear bombs. (perfect tense, plural and passive)

Now, sometimes the usage focuses the action that was completed in the past as above. However, sometimes the focus is on the ongoing state or effects. For example.

He knows (perfect tense) his wife.

Translating it “he has known” his wife would sound really strange, especially if it’s a perfect tense participle. incidentally, a woodenly literal translation of a perfect tense participles in that example would look like this:

He has knowing (perfect tense) his wife.

It kind of sounds like nonsense. That’s why perfect tense is usually translated as the simple present tense in such cases. (“He knows his wife.”)

Since the present aspect has already taken up the letter “P”, we’ll indicate the perfect aspect with a capital “R” – for perfect – as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-RIM-3S”

The Pluperfect Aspect

The pluperfect aspect is similar to the perfect aspect with one major difference. The pluperfect aspect is an action that (1) was completed in the past, and (2) had results that ended in the past and don’t extend to the present. To keep with our previous example for context:

The nuclear bomb had irradiated (pluperfect tense) the area.

The bomb irradiated the area in the past, but the radiation is now gone; the effect of the radiation ended in the past. The pluperfect tense is used less than 100 times times in the New Testament, so it’s not very common. Typically, you’d use the word “had” to indicate it. For example: “he had worked” “She had sewn”, “they had fought” etc.

Since the present aspect has already taken up the letter “P”, we’ll indicate the pluperfect aspect with a capital “L” – for pluperfect – as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-LIM-3S”

The Future Aspect

This one is easy; the future aspect in Greek is exactly like the future tense in English. That’s it, so it’s simple. It’s used to indicate actions that will happen in the future, and occasionally commands; just like in English. Just like in English, it’s usually translated with “will” when referring to the future, or “shall” when being used as a command.

He will fight

You shall not fight

And that’s about it.

We’ll indicate the Future aspect with a capital “F” as the first letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-FIM-3S”

Aspect Conclusion and Recap

Here’s a quick recap and reference:

- The Aorist Aspect tells you an action is complete, and looks at the whole action at once, like a picture. In the indicative mood, it indicates simple past tense

- The Present Aspect tells you the action is ongoing and continuous, like a movie playing. In the indicative mood it indicates present tense (either simple present or present progressive)

- The Imperfect Aspect tells you the action was ongoing in the the past, and it only occurs in the indicative mood.

- The Perfect Aspect tells you the action was (1) completed in the past and (2) has results or an ongoing state that continues up into the present time.

- The Pluperfect Aspect tells you the action was (1) completed in the past, and (2) had results that also ended sometime in the past.

- The Future Aspect tells you the action will take place in the future, and can indicate commands.

Now that we have covered (perfect tense 😉 ) Koine Greek verbal aspects, we’ll move on to Voice, Plurality, and Person. We have these in English (except the Middle voice), so this should be very easy and quick.

Verbal Voice

English has two voices: active and passive. Koine Greek has three: active, middle, and passive. We’ll start with the two voices English does have, and use that as a springboard to discuss the one English doesn’t have: the middle voice.

I will mention this now and explain it more fully later: the meaning of a word in Koine Greek verb can change in the middle voice.

The Active Voice

In English and Greek, the active voice is essentially the same. The active voice indicates that the subject of the sentence performed the action. For example:

John punched (active voice) Tom

That’s it, it’s pretty simple. We’ll indicate the Active voice with a capital “A” as the third letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-3S”

Now, for the rest of this article I will use the present tense form of verbs in English, and relying on the inflections added to tell you what the verb actually means. (except for explanations/examples)

For example, the Aorist Indicative Active form of the verb “punch” is “punched”. However, I will use the present tense for “punch” with inflections (example: “punch-AIA-3S”), even to indicate a simple past tense event. (Which would be aorist indicative in Greek). So the example quote above would be:

John punch-AIA-3S Tom

In that same spirit, we’ll take this opportunity in to do a short recap. Take the following example:

(Tom-AMS) (Mary-NFS) (kiss-AIA-3S)

In your head, you should be able to make sense of the above sentence, even though we haven’t looked at the “3S” part yet. Once you think you know what it means, click below to expand the answer.

click here to expand the answer- First, locate the verb and notice the voice. It’s in the active voice, so that means the subject did the action.

- Mary is NFS. N = Nominative (subject case), so she did the action.

- Tom is AMS, A = Accusative (direct object case), so he received the action.

Anyway, now moving on to the passive voice.

The Passive Voice

In English and Greek, the passive voice is essentially the same. The passive voice indicates that the subject of the sentence received the action of the verb. The example below describes the exact same event that the active voice example described (“John punched Tom”). However, it describes it using the passive voice.

Tom was punched (passive voice) by John

Notice, the subject of the sentence changed even though the same event is being described. I’ll put both sentences next to each other with the inflections so you can see.

John-NMS punch-AIA-3S Tom-AMS

Tom-NMS punch-AIP-3S by John-GMS

(Note: Notice the genitive in the second sentence and perhaps consider why that’s the proper case…)

Notice that John is the subject (nominative case) in the first example, while Tom is the subject in the second example.

We’ll indicate the Passive voice with a capital “P” as the third letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIP-3S”

Now we’ll tackle the middle voice.

The Middle Voice

The middle voice is complicated to us, but was natural to the Greeks. The basic idea boils down to this: In the middle voice, the subject initiates the action, and is involved in the effects of the action. The middle voice means that the subject (nominative case) is acting on, to, or for himself in some way. That is, the subject (nominative case) has some personal and/or vested interest, or a connection with the action he is performing.

The best way to understand the Greek middle voice is that it expresses more direct participation, involvement, or even some kind of benefit to the subject doing the action.

However, don’t think of the middle voice as reflexive.

A lot of people think of the middle voice like it’s reflexive, and that’s simply not the case. For those who don’t remember what reflexive means from school, I’ll explain it. Reflexive is when the subject and the direct object are the same. i.e. the subject acted upon himself.

In English, we indicate this with pronouns ending is self/selves. For example:

I like myself. (reflexive)

You like yourself. (reflexive )

He likes himself. (reflexive)

You use the reflexive format when the subject does something to himself. However, the Greek middle voice does not mean reflexive. It’s easy to confuse the two because the middle voice can be – and sometimes should be – translated as reflexive in some cases.

Confused yet?

To explain this, I’m going to use an ancient example that was used to teach the difference between the active voice and the middle voice, and then I’ll add a reflexive construction for comparison.

He sacrificed a cow for her benefit. (active voice)

He sacrifice a cow for his benefit. (middle voice)

He sacrificed himself. (reflexive construction; obviously he didn’t sacrifice himself in the first two examples.)

Again, in the Middle voice, the subject initiates the action and is involved in the effects of the action.

Again, the best way to understand the Greek middle voice is that it expresses more direct participation, involvement, or even some kind of benefit to the subject doing the action.

In the active voice (the first example), the subject “he”, initiated the action, but has no involvement in the outcome. The benefit is outside of the subject, to “her” in this example.

However in the middle voice, the subject “he” not only initiates the action, but is also involved in the effects of the action. That is, the subject does the sacrificing and the benefit goes to the the person who acted. That said, the middle voice isn’t always about benefit, or even usually about benefit. It can be, but certainly not always.

Again, the best way to understand the Greek middle voice is that it expresses more direct participation, involvement, or even some kind of benefit to the subject doing the action.

In contrast, the reflexive the action is done to the subject.

The middle voice can sometimes be properly translated as reflexive, often with verbs that involve personal care, especially grooming. These often are translated reflexively because that’s the sense. For example:

- I wash dishes. (active voice; action on someone or something else.)

- I wash. (middle voice; readers would understand that he washed himself.)

Now, because of the differences between the active and middle voices, some Koine Greek words have a slightly different meanings in the active voice vs the middle voice.

No, seriously.

Here’s an example. There’s a Greek verb with the following meanings, and I’ll add the passive voice so you can see all three together:

- Active voice meaning = to make someone or something stop

- Middle voice meaning = to cease

- Passive voice meaning = to be stopped

In the active voice, the subject initiates the action and acts on something outside of itself. However in the middle voice, the subject initiates the action and is involved in the effects. The subject is directly involved with, and participates in, the ceasing. Here are some more examples, and notice the subject’s involvement in the effects of the action.

- Active voice meaning = to persuade

- Middle voice meaning = to comply with

- Passive voice meaning = to be persuaded (by someone or something else)

- Active voice meaning = To put (others) in battle array

- Middle voice meaning = To put yourself in battle array

- Passive voice meaning = To be put in battle array (by someone else)

- Active voice meaning = To guard someone or something

- Middle voice meaning = To be on guard against someone or something

- Passive voice meaning = To be guarded (by someone or something else)

English doesn’t have the middle voice, but some of our verbs are very “middle voice” in nature.

We’ll indicate the Middle voice with a capital “M” as the third letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIM-3S”

Voice Recap & Middle/Passive

Here’s a quick recap on the voices

Active voice: the subject initiates the action. (John guarded Mary)

Middle voice: the subject initiates the action, and is involved in the effects of the action. (John was on guard against Mary)

Passive voice: The subject is acted upon. (John was guarded by Mary)

Not too hard.

Now, there’s one other thing that’s very important: Many Greek verbs are identical in the middle and passive forms, so you can’t tell the difference except by the context. Yes that’s odd, so here’s an English example that’s similar, only using tense instead of voice.

- He can read the book.

- He read the book.

The present tense verb “read” (pronounced “reed”) looks exactly the same as the past tense verb “read” (pronounced “red”). It’s the same verb, but there’s no way to tell if the past or present tense is intended by looking at the word itself. Instead, you have to look at the context.

It’s the same with Greek verbs that are in the Middle/Passive.

You need to look at the context to see whether the middle or passive voice is intended. Often it’s obvious, sometimes it’s not.

(For those who are curious why the forms are the same for many verbs, it’s because originally Greek didn’t have a passive voice; only active and middle. The passive voice grew out of the middle voice.)

We’ll indicate the Middle/Passive voice with a capital “M/P” as the third ‘letter’ in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIM/P-3S”

Verbal Plurality

This section and the one after it will be incredibly short because English is essentially identical to Greek in these aspects. Plurality in Greek is exactly like English:

- Singular = 1 person is doing the action

- Plural = 2 or more people are doing the action.

That’s the essence of plurality in both Greek and English.

- We’ll indicate Singular with a capital “S” as the fifth letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-3S“

- We’ll indicate Plural with a capital “P” as the fifth letter in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-3P“

Now, in English we have sort of the number of people doing the action embedded in the verb, but not fully. For example:

Fight (Plural form: “they fight”, since “they fights” isn’t correct and sounds wrong.)

Fights (Singular form: “he fights”, since “he fight” isn’t correct and sounds wrong.)

However, this singular/plural distinction in English doesn’t always apply. For example, “I fight” and “we fight” are the same, even though one is singular and one is plural. In Greek, it’s much more explicit that it’s singular or plural. So much so that you can write a single verb and have it be a complete sentence. For example:

Fight-PIA-3S = is a complete sentence: “he/she/it fights.” (or “he/she/it is fighting”)

Fight-PIA-3P is a complete sentence: “they fight.” (or “they are fighting”)

That’s a complete sentence with only one word.

It should be noted that Greek infinitives and participles don’t have “plurality” like verbs do, though participles have “number” like nouns and adjectives do, which serves the same function.

Verbal Person

Again, this is exactly like English. In both Greek and English, “person” indicates who did the action. First person means “I/we”, second person means “you”, and third person means “he/she/it/they”. For example:

- I fight. (first person singular)

- We fight. (first person plural)

- You fight. (second person singular)

- You fight. (second person plural)

- He/she/it fights (third person plural)

- They fight. (third person plural)

That’s all pretty simple, until you realize that “you” singular and “you” plural are the same in English, but not in Greek. It should be:

- Thou fight. (second person singular)

- You fight. (second person plural)

However, we’ve sadly lost “thou” in the English language. This actually makes the Bible harder to interpret accurately, since you can’t tell when “you” is singular vs plural in English. However you can in Greek (and Hebrew too). Originally in English it was like this though:

- Thou = you (subject/nominative case)

- Thee = you (direct object/accusative case)

- Thine = your/yours (possessive case)

Anyways, that’s verbal person.

- We’ll indicate First person with a “1” as the fourth item in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-1S”

- We’ll indicate Second person with a “2” as the fourth item in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-2S”

- We’ll indicate Third person with a “3” as the fourth item in our abbreviation, like so: (for example) “-PIA-3S”

Now, we’ll move onto an important topic: translating participles.

Translating Participles

English participles are rather limited, but Greek participles have an amazing array of options for their use. Remember that participles are verb forms that can also function as an adjective. This is part of what makes them so flexible. Remember also since participles are a hybrid, they also have hybrid properties.

Remember: Greek Participles have aspect, mood, and voice like verbs, but lack person and plurality like other verbs. However, they gain case, gender, and number like other adjectives.

One other thing to mention before we go on: The gender of the participle indicates the gender of the person or persons doing the action. (or receiving the action in the passive voice) This is quite important for understanding some passages, so don’t forget this.

Now, we’ll move on to the two main uses of participles.

The two main uses are: participles used to form a short relative clause (called “attributive participles”) and… other participles (called “Circumstantial participles” or “predicative participles”)

The difference between the two is the definite article.

- If a participle is preceded by a definite article that matches case, gender, and number, it’s an attributive participle.

- If a participle is not preceded by a definite article that matches case, gender, and number, it’s a circumstantial participle.

That makes them easy to tell apart. 🙂

Attributive Participles

These are the easier ones. Attributive participles are always preceded by a definite article that matches case, gender, and number. Always.

Now, in English participles usually have the “ing” suffix, but not always. For example:

- Running (he is running” vs “a running trophy”)

- fighting (“he was fighting” vs “a fighting man”)

- kissed (“she will be kissed” vs “a kissed woman”)

- clothed (“he clothed himself” vs “a clothed man”)

Now, here’s what an attributive participle would look like in English if we had them. (we don’t, or at least not constructed the way Greek does)

The running

The kissed

And here’s what it would look like in Greek, without the rest of the sentence and with the inflections added.

the-NMP run-APA-NMP

the-NFS kiss-APP-NFS

You can translate each of those two sentences two ways:

- The men who ran

- The running men

- The woman who was kissed

- The kissed woman

Either of those is technically correct. However, a slight modification of version #1 is almost universally preferred as a translation for several reasons. Here’s the slight modification that’s often used:

Those who ran

She who was kissed

Now, notice that the first commonly-used option (using “those”) neuters the gender so you can’t see it.

This is actually a serious problem in some passages where gender is important to the passage, but disguised. Even good translations like the NASB ’95, LSB, and NKJV translate it as “those”. That’s not accurate to the original genders. Again, it causes problem in some passages, and even has a cumulative effect which leads to all kinds of errors in biblical exegesis. (I could write a whole article about that, and probably will at some point.)

Almost every single time you see “those who ____” in the New Testament, where the “____” is a verb, it should be translated “the men who ____”.

That’s accurate to the original genders. Now, you might be wondering about a neuter participle, for example:

the-NNP create-AIP-NNP

Typically, you add the word “things” if nothing is specified. For example:

the things which were created

Anyway…

We’ll go back to a previous example:

the-NFS kiss-APP-NFS

Translating this as “she who was kissed” or “the kissed woman” doesn’t read nearly as smoothly as “the woman who was kissed” when it’s used in a sentence. For example:

The kissed woman went on a date.

She who was kissed went on a date.

The woman who was kissed went on a date.

Despite being the longest, the last one reads the smoothest, though some may prefer “the kissed woman”. However, there’s an important reason not translate it “the kissed woman” in particular, and that’s to preserve verbal voice and aspect. Take the two following sentences, in which everything is the same except aspect and voice:

the-NFS kiss-APP-NFS

the-NFS kiss-PPA-NFS

In English, both would be translated: “the kissed woman” if you did simply adjectival construction, and you lose verbal voice and aspect.

There would be no way to know (in English) if the woman kissed someone or if someone kissed her if you translated it “the kissed woman”. In fact, that sounds a bit passive passive, when it could be active in Greek. Thus, it’s better to translate like the following examples to preserve aspect and voice:

The woman who was kissed

The woman who kisses

Thus, when a participle is preceded by the definite article, it should be translated as a short relative clause, such as in the examples we’ve been showing.

Now we’ll look at the other usage for participles.

Circumstantial Participles

Don’t let the fancy name fool you, Circumstantial Participles participles simply mean participles that are used without a matching definite article. We have these in English too, though they are less commonly used.

Seeing the ghost, they ran

They hid, knowing that’s the point of hide-and-seek

Those are examples of circumstantial participles in English. It’s the “circumstances” surrounding the participle that decide the specific idea it’s trying to get across. Circumstantial participles in Greek can communicate five different things:

- Time in temporal participles

- The cause of some action or effect in Causal participles

- The instrument through which something is done or accomplished in instrumental participles

- The purpose for which something is done in participles of purpose

- Concessions in concessive participles

Now, you probably don’t need to memorize these because it’s usually obvious from the context, plus it’s sometimes more than one at a time. For example:

Seeing the ghost, they ran

You can tell by reading it that it’s a temporal participle (indicating time) and a causal participle (indicating why something was done). That leads me to a caution when translating circumstantial participles: beware of over-translating. By that, I mean making a choice which eliminates options that the original language offers.

Here’s an example to show what I mean:

see-AIA-NMP the ghost, they ran.

(Bonus points if you can tell the gender of the people who ran.)

Now, there are several ways that this might be commonly translated:

- Seeing the ghost, they ran.

- Having seen the ghost, they ran

- After seeing the ghost, they ran

- After they saw the ghost, they ran

- Because they saw the ghost, they ran

Of those, which comes closest to the original aorist indicative active participle in the nominative masculine plural? Which option preserves the meaning and intent of the original the best?

Think about it for a moment and then click here to expand the answer

Answer: either 1 or 2, with a significant edge to #2.

- Translation #3 adds “after”, which is correct because it does indicate time here. However, that also eliminates the sense of “because” which is present in the original.

- Translation #4 is worse, since it not only eliminates “because”, but also makes the participle into a “regular” verb. (Though sometimes you need to do that because the sentence would sound terrible if you kept it a participle. But if you don’t need to, don’t, and you usually don’t need to.)

- Translation #5 is exactly like option #4, except it eliminates the time aspect to instead of the “because” aspect.

By contrast:

- Translation #1 keeps it a bare participle, leaving both causal and temporal aspects intact and possible.

- Translation #2 is still a participle construction, though a compound one. It’s also slightly more “aorist” in nature because “having seen” tends to indicate a completed action better than “seeing”. (If it was present aspect, I would prefer “seeing”.)

Now we’ll look at some biblical examples: (usually just part of the verse for space’s sake; my translation for this article.)

Mark 9:15: And immediately all the crowd, see-APA-NMP Him, were stunned. (in context, this is primarily a temporal participle since He had just arrived, and hadn’t done a miracle or anything.)

John 4:6: Jesus, tire-RPA-NMS from the journey, was sitting at the well. (Nearly a pure causal participle since the journey was the reason He was tired. There is a hint of temporal though.)

Matt 27:4: I sinned, betray-APA-NMS innocent blood. (Judas speaking, indicating the instrument through which he sinned. Also a good dose of causal.)

Luke 10:25: A lawyer stood up, test-PPA-NMS Him. (A pure participle of purpose; the lawyer stood up in order to test Jesus. These can be the hardest to translate while keeping the form as a participle in English. For this particular example, I would probably do “A lawyer stood up, intent on testing Him.” and the underlined words would be italicized to indicate a translator addition.)

Romans 1:21: Because know-APA-NMP God, they didn’t glorify Him as God. (a concessive participle “although knowing” or “although having known”. Though one could argue it’s a temporal participle as well and could be understood as “while”.)

Please notice how often two or more types of participle were represented in these examples. That’s why it’s ideal to leave it a bare participle whenever possible.

Pronouns

This section will be pretty easy because they function much the same as in English. We’ll cover:

- Personal pronouns (I, you, he/she/it, etc.)

- Demonstrative pronouns (this, that, these, those)

- Relative pronouns (who/whom, which, what, that)

- Reflexive pronouns (myself, yourself, himself, etc.)

Personal Pronouns

This section will be short because Koine Greek pronouns are almost identical in use to our English pronouns. However, pronouns aren’t treated like regular nouns whish have case, gender and number. Koine Greek personal pronouns can have up to four properties, one of which you’ll recognize from verbs.

- Case (like nouns)

- Gender (like nouns)

- Person (like verbs)

- Number (like nous)

Thus, they are a bit different than regular nouns, but not much. There are three personal pronouns, one for each “person” (first person, second person, third person). However, they all function similarly to each other. There are some small differences, which we’ll get into in a moment.

First, remember that Koine Greek verbs have person imbedded in them; you don’t necessarily need to use a pronoun. So for example, In English you might write:

We are going to the store.

But in Greek, you don’t need the personal pronoun “we” because it’s embedded in the verb.

Go-PIA-1P to the store.

Which would be translated “we are going to the store” because of the first person plural inflection. Typically, you only use a nominative (subject case) pronoun when you want to be emphatic about the subject.

First and Second Person Personal Pronouns

The first and second person pronouns (I/we, you/your) are like the third person pronoun except that they lack gender; they only have case, person, and number. That’s really the only difference, and makes sense. Theoretically, the gender of both the person speaking and person being spoken to will be obvious, which is probably why it’s not included.

Notice, the English first and second person pronouns (I/me/my, you/your/yours) don’t have gender either. Our third person personal pronouns have gender (he/she/it), but the first and second don’t.

In this article, we’ll use “PPro” for Personal Pronouns, and add the case, number and person distinctions, like so: (for example) “PPro-A1S” or “PPro-N2P.

Third Person Pronouns

This is the weird one. The Koine Greek third person personal pronoun (he/she/it) has all four properties of case, gender, person, and number, as well as an additional meaning.

In this article, we’ll use “PPro” for Personal Pronouns, and add the case, gender, number and person distinctions, like so: (for example) “PPro-A1S” or “PPro-N1P. Further, we won’t use constructions like: “he-PPro-NM3S”, it’ll just be the abbreviation “PPro” standing in for the word, with the inflections added.

For example, instead of saying:

He talked to you and me.

Or even:

He-NM3S talk-AIA-3S you-AF2S and me-A1S

We will use:

PPro-NM3S talk-AIA-3S PPro-AF2S and PPro-A1S

The goal is to get you to rely on the inflection, not the English word.

Now, the Koine Greek third person pronoun has a second function, which is completely ignored by some New Testament writers and heavily used by others. It means “self” or “same”, and can function as an intensifier. For example:

Jesus-NMS PPro-NMS taught them.

This would typically be translated as:

Jesus Himself taught them.

The addition of the pronoun adds emphasis. It can also mean “same”, but that’s a less common usage I’ll skip for the sake of space.

Now, there are other kinds of pronouns besides personal pronouns. We have them in English, so they shouldn’t be hard to understand.

Reflexive Pronouns

We already talked about reflexive pronouns when we talked about the middle voice, but we’ll hit them again here. In both English and Greek, you use a reflexive pronoun when you want to indicate that the subject is also the direct object. (The direct object is what receives the action of the verb). For example.

The man hit himself.

The woman embarrassed herself.

The things destroyed themselves.

Reflexive means that the person or thing that did the action also receives that same action. In English, all reflexive pronouns end in “self” or “selves” (depending on if it’s singular or plural.) In this article, we’ll use “RefPro” for Reflexive Pronouns, and add the case, gender, number and person distinctions, like so: (for example) “RefPro-AM1S” or “RefPro-NF1P.

So those examples would look like:

The man hit RefPro-AM3S. (himself)

The woman embarrassed RefPro-AF3S. (herself)

The things destroyed RefPro-AN3P. (themselves)

The Greek reflexive pronoun has case, gender, person, and number, just like Greek personal pronouns. However, unlike the personal pronouns, the “person” of the Greek reflexive pronoun is always 3rd person, even when it’s used in the first or second person. Seriously. (Greek has quirks too)

For example: (partial verses only for the sake of space.)

Romans 8:23: we groan in ourselves-DM3P, eagerly awaiting the adoption as sons (first person)

Matthew 3:9: And don’t presume to say among yourselves-DM3P; “We have Abraham as a father” (second person)

1 Corinthians 3:18: Let no man deceive himself-AM3S. (third person)

Notice that even though it looks like a third person reflexive pronoun, it functions as a first and second person reflexive pronoun too. (There’s technically also a first person emphatic reflexive pronoun, but we’ll ignore it for the purposes of this article.)

Now in Greek, reflexive pronouns can also be used to indicate extremely strong and exclusive possession. Here’s an example from the Bible:

1 Cor 7:2 (partial verse)

Let each man have the-AFS RefPro-GM3S wife-AFS.

When the reflexive pronoun is used like this, it’s usually translated “his own”. (or “her own”, their own” etc.). Here it is with a hyper-literal translation, a literal one, and then the common one; like so:

1 Cor 7:2 (partial verse)

Let each man have the of himself wife. (hyper-literal)

Let each man have his wife to himself. (literal, which I prefer; note the added possessive pronoun “his” for clarity.)

Let each man have his own wife. (common, but not reflexive)

(Interestingly, the second half of the verse – which is usually translated “and let each wife have her on husband” – doesn’t use a reflexive pronoun like the first half. The possessive forms are quite different, but sadly often translated the same.)

When used this way, the definite article’s grouping function comes into play. Notice how the non-matching word (himself) was sandwiched between an article and a noun that matched each other: “the-AFS RefPro-GM3S wife-AFS“. The definite article tells you what goes with what via its grouping function.

This grouping function is used this way many places, not just possession. As a matter of fact, a common way to say – for example – “her son” would be “the son [of] her“, though the [bracketed] word is implied by the construction.

Anyway, moving on to relative pronouns.

Relative pronouns

These are dirt simple, since they function almost exactly the same as in English. Relative pronouns in English are who/whom, which, what, and that. The Greek relative pronoun (singular) functions the same way. Relative pronouns always point to something that previously occurred in the sentence, or perhaps in an earlier sentence.

For example:

The man who walked was late.

The thing which fell broke

The relative pronoun “who” refers back to something earlier in the sentence, into his case “man”. It’s the same with “thing” and “which” in the second sentence. There are several different relative pronouns in English:

- Who: Refers to a person (as the verb’s subject)

- Whom: Refers to a person (as the verb’s object)

- Which: Refers to an animal or thing

- What: Refers to a nonliving thing

- That: Refers to a person, animal, or thing

In Greek, these are all the same word. In Koine Greek, all of those words on the list above are the same Greek word. That makes translating it… interesting.

Mostly, use the rules above and you’ll do fine.

Greek relative pronouns have case, gender, and number just like nouns and adjectives, so we will use the same shorthand for them that we used for nouns and adjectives. In this article, we’ll use “RelPro” for Relative Pronouns, and add the case, gender, number distinctions, like so: (for example) “RelPro-NMS” or “RelPro-AFP”. We’ll do this instead of “what-NMS”, since depending on the context it will be who, what, which, etc.

For example:

- The man who fought, won.

- The pig which ate was satisfied.

- What was written came to pass.

These would be expressed as:

- The man RelPro-NMS fought won.

- The pig RelPro-NNS ate was satisfied.

- RelPro-NNS was written came to pass.

Notice that #2 and #3 are identical in form, (“RelPro-NNS“) but should be translated different ways (“which” vs “what”). That’s because English has more specificity in relative pronouns than Greek does.

Now, the noun which the relative pronoun refers back to is called an antecedent.

In sentence # 1 above, the antecedent for the relative pronoun is “man”. In the second sentence, it’s “pig”. In the third… well, sometimes the antecedent is implied or not specified.

Now, in order to associate a relative pronoun with its antecedent, they must match gender and number. The case can match, but doesn’t have to.

For example:

The man-NMS RelPro-NMS drove the car.

In this case they match case, gender, and number, which tells you they are associated. Again, they don’t need to match case, but do need to match gender and number.

Again, they aren’t associated if they don’t match gender and number: (Note: I used “who” instead of “RelPro” for clarity in this example)

The man-NMS and the woman-NFS (who-NMS kept-AIM-3S a secret) took a walk.

Notice that the relative pronoun matches man, but doesn’t match woman. Notice also the verb “keep” is singular, so only one person is keeping a secret. In order to make the association clear in English, you need to change the word order:

The man (who kept a secret) and the woman took a walk.

You need to translate it this way because if you used the original word order without gender specificity, you’d give the incorrect impression; like so:

The man and the woman (who kept a secret) took a walk.

This makes it sound like either (1) the woman was keeping the secret, or (2) they were both keeping a secret. Obviously neither is true given the singular verb and gender mismatch between “who” and “woman” in the original. In fact, there’s a very famous example in the Bible of this mistake, and an entire doctrine was built on this mistake. (Technically, the example below uses demonstrative pronoun not a relative pronoun, but they have the exact same word association rules so it applies.)

Here it is:

Matthew 16:18 (my translation for this example)

And I tell you that you are Peter-NMS, and on this-DFS rock I will build My Church